Articles

The experience of the Mexican state with the conditional cash transfer programmes to alleviate poverty

La experiencia del Estado mexicano con los programas de transferencias monetarias condicionadas para reducir la pobreza

The experience of the Mexican state with the conditional cash transfer programmes to alleviate poverty

Espacios Públicos, vol. 18, no. 44, pp. 71-100, 2015

Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México

Received: 30 October 2014

Accepted: 07 June 2015

Abstract: For more than fifteen uninterrupted years, conditional cash transfer programmes (ccts) have been used with the purpose of alleviating poverty in Mexico. However, there is little evidence that proves that the programme is achieving its main goal. In recent decades, it has been demonstrated that within developing countries poverty has been alleviated more effectively in countries where the labour market has been strongly institutionalized. Using a mixture of qualitative and quantitative methods, we assessed the extent to which the weakness of the institutional capacities of the Mexican state, among other important factors, has impeded the current Mexican cct programme known as Oportunidades from achieving its main goal. Our results show that the weakness of the institutional capacities of the Mexican state makes poverty alleviation much less likely to occur because it impedes the provision of training and labour market policies that complement the programme and enable the poor to move out of poverty.

Key words: State, institutions, poverty, inequality, employment. .

Resumen : Por más de quince años los programas de transferencias monetarias condicionadas (tmcs) se han utilizado en México con el fin de reducir la pobreza. Sin embargo, hay poca evidencia que demuestre que el programa esté logrando su objetivo principal. En las últimas décadas se ha demostrado que entre los países en vías de desarrollo la pobreza ha disminuido en aquellos países en los que el mercado laboral ha sido fuertemente institucionalizado. Utilizando una mezcla de métodos cualitativos y cuantitativos, se evaluó el grado en que la debilidad institucional del Estado mexicano, entre otros factores importantes, ha impedido al tmc mexicano, conocido como Oportunidades, alcanzar su objetivo principal. Nuestros resultados muestran que la debilidad institucional del Estado mexicano impide la provisión de políticas de empleo y capacitación que complementen al programa y permitan a los beneficiarios salir de la pobreza.

Palabras clave: Estado, instituciones, pobreza, desigualdad, empleo..

Introduction

The 1980s represented a breaking-point in the social, economic and political history of Mexico. From the 1930s to the early 1970s, based on the Import Substitution Industrialization (isi) system, Mexico's Gross Domestic Product (gdp) grew at a relatively rapid pace (3% per year in per capita terms), as a result of which it was known as the 'Mexican miracle' (Esquivel, 2010: 4-5). However, not only was the Mexican state unable to develop any productive sector that allowed the country to compete internationally, but it also depended mostly on international loans and the profits from oil to sustain the isi system (Moreno-Brid, Pardinas and Ros, 2009: 156- 158). In this context, the globalization of the economy and the fall of the oil prices during the late 1970s had serious effects on the Mexican economy and in 1982 Mexico suffered a high debt crisis, bringing about large devaluations and high levels of inflation, which triggered a huge increase in the levels of unemployment, income inequality and poverty (understood at that time as nutritional).

Consequently, following recommendations from the International Monetary Fund (imf) and later on from the World Bank, like most of the Latin American countries, Mexico started a process of structural adjustment and economic reforms with the intention of achieving macroeconomic stability, increasing employment and reducing income inequality and poverty (Robertson, 2007: 1380). The socalled Washington-Consensus reforms started to be implemented in the early 1980s and basically comprised two main market-oriented strategies, the reduction of the size of the state and the openness of economic sectors, in order to allow the markets to adjust properly - on their own dynamics - to the new conditions and challenges that the new global order presented. Paradoxically, the socio-economic conditions of the citizens during this period were worsened especially due to the deep cuts in social spending, which meant a regression in the advancement of the social rights that had been attained in the first half of the twentieth century. In the last two decades Latin American countries have undertaken a path towards the equalization of the poor´s socio economic conditions with the implementation of the conditional cash transfer programmes (ccts), which would allow them to have access to basic services such as health and education, acquiring capabilities that enable them to obtain sustained income in the labour market to move out of poverty by their own efforts.

Evaluations of the Mexican ccts Progresa- Oportunidades have been quite encouraging (Molyneux, 2008; Soares, Ribas and Osório 2010; González, 2012; and others). These evaluations have demonstrated significant impacts on the well-being of the recipients, such as increasing school attendance, improving health outcomes and reducing income inequality while families or recipients belong to the programme, among other short-term effects. However, there is little evidence that shows that the programme's ex-recipients are able to obtain sustained income in the labour market, which might leave them vulnerable to the shocks of the economy and to falling into poverty again. A relevant question now would then be if the evaluations of Progresa-Oportunidades have shown positive results in increasing the educational levels of the ex-recipients what is impeding the state from alleviating poverty? 73 In recent decades, there has been a general consensus that within developing countries, strong institutionalization of the labour market has not only ameliorated the impacts of the global transformation initiated in the 1970s and 1980s but has also been more important in alleviating poverty than high educational levels (Chang, 2010: 179; Grinberg, 2010:185; Evans & Sewell, 2013:48; and others).

The aim of this paper is to examine the extent to which the weakness of the institutional capacities of the Mexican state has impeded the ccts from enabling the poor to obtain sustained income in the labour market that would allow them to move out of poverty in urban zones. We chose urban poverty for three main reasons: First, in Latin American countries in absolute terms there are more poor people in the urban zones than in rural areas, since the majority of the population now lives in cities (World Bank, 2006:149). Second, people in towns cannot depend on self-produced consumption in the way that their rural counterparts can, and this is the reason why they become more dependant on the state provision of resources and services to increase their capabilities to obtain sustained income in the labour market. Third, due to the high levels of labour informality that exist in Latin America, the main concern of state policy regarding employment is that poor people have sustained income generation, which is the reason why the relationship with the institutional capacities of the state regarding their opportunities in the labour market is more direct in urban zones.

Our results show that the weakness of the institutional capacities of the Mexican state makes poverty alleviation much less likely to occur because it impedes the provision of training and labour market policies that complement the programme and enable the poor to obtain a sustained income. The paper is divided into five main sections. In the first, we review the environment that paved the way for the structural adjustment reforms that were implemented in the 1980s and its effect on the institutional capacities and the welfare model of the Mexican state. In the second section, we review the way in which the ccts have evolved in the last three decades. In the third section, we present our methodology. In the fourth section we analyse the Mexican labour market. The fifth section concludes the paper.

The structural adjustment and its effects on the institutional capacities of the state and the welfare system

In the post-war period (1940s-1970s), known as a period of 'stabilizing development', Mexico's economic development strategy relied upon state intervention to encourage the industrialization of the country, mainly of urban areas, and protecting domestic manufacturers from international competition by means of isi programmes. During this period, one of the main political actors was the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (pri) political party, which ruled Mexico from 1929 to 2000. In the course of the stabilizing development period, this political party built a corporatist and clientelist relationship with the private sector and different social actors, directing social protection schemes only to those well-organized enough to demand them, such as state workers (the armed forces, the judiciary, and so on) and the formal workers of the private sector, excluding workers in the informal sector. In addition, since basic services such as education and health are considered as rights in the Mexican Constitution, the state complemented that model with the universal provision of those services and universal subsidies for rural and urban areas (Scott, 2009: 11).

However, not only was the universal coverage of basic services never achieved, but also the quality of the services provided was low. Notwithstanding, the isi programmes and the quasi-universal welfare system implemented from the 1940s to the 1970s were, to some extent, successful. Mexico's annual labour productivity growth rate was around 2.1% and gdp per capita grew annually between 3.0% and 4.0% in real terms (Cárdenas, 2009: 271), as a result of which it was known as the 'Mexican miracle'. The social contract implemented was an inclusive one since the economic and social models were seen as complementary, "the poverty alleviation strategy and the wider development strategy were one and the same" (Székely & Fuentes, 2002: 125), and the informal and formal sectors were close to one another, in consequence integrating most of the actors of the social structure, and bringing about low rates of unemployment and poverty (Escobar & González, 2008: 40-41).

Nonetheless, the social rights provided were, on the one hand, just a way of keeping the different social groups under control to keep the isi system working and on the other hand, the industrial policies could not find a sector that could compete strongly internationally (Moreno-Brid, Pardinas and Ros, 2009: 157). Moreover, although the country produced much of the merchandise that was traded, the technology with which the products were produced was imported. In the late 1970s, Mexico was attempting to replace the technology as well. However, the industrial programmes of the state tended to "operate in combination with regressive or only mildly progressive tax structures and low tax revenues" (Teichman, 2008:447), leaving the oil profits and international aid as the only sources of finance, bringing about procyclical social spending and economic volatility.

Most of the Latin American countries have historically suffered from the resource curse. Mexico has been no exception; the decline of oil prices at the beginning of the 1980s joined with the globalization of the economy forced the political authorities to implement measures to control the macroeconomic stability of the countries. After the 1982 collapse of oil prices, tied to rising inflation and high interest rates on its external debt, Mexico confronted its most serious economic crisis since its birth as a nation-state in 1917, with poverty and socio-economic inequality as the most prevalent effects, which implanted the belief that the conservative-informal welfare model was exhausted. Consequently, President López Portillo (1976-1982) declared that it was not possible to continue paying Mexico's external debt, which brought about a domino effect over the whole of Latin America, where most of the countries found themselves in a similar situation with unpayable external debts (Sánchez, 2006: 775).

Due to the debt crisis, Latin American governments were no longer able to finance public spending through foreign borrowing because the region was shut off from international capital 75 markets (Sánchez, 2006: 775). Thus, conditioned and encouraged by the imf, Latin American countries initiated a process of state reform that would mark the end of the conservative-informal state and begin the era of the 'liberal-informal state' (Barrientos, 2004: 156). Seeking to reduce the huge fiscal deficit, lower inflation rates, address macroeconomic instability and adjust to the new global order, the Mexican government cut public spending, eliminating most of the state subsidies, reduced the size and scope of the state by dismantling or privatizing state-run companies, and opened up the economic and finance sectors.

The problem was, as Fukuyama pointed out, that "in the process of reducing the scope of the state those reforms decreased its strength or generated demands for new types of state capabilities that were either weak or nonexistent" (Fukuyama, 2005: 20). During the industrializing period, the state's revenue was mainly levied on industrial production, natural resources (mainly oil-related profits) and international trade with special schemes for workers in the primary sector and tax exemptions for corporations that invested in key industrial sectors and indirect taxation was based on a single turnover tax (Alvarez, 2007:5).

The fiscal system was part of the first generation reforms during the early 1980s and it was reformed to enhance the openness of the economy and achieve macroeconomic stability and fairness in income distribution.1 The main reforms were the enacting of the Fiscal Coordination National System (fcns) Law, with the purpose of avoiding double or triple taxation and improving the fiscal relationships among the three levels of government, the reform of Article 15 of the constitution in 1983, which delegated to the municipalities the responsibilities for providing some public services, the recognition of inflation effects in the tax bases, the reduction of personal income tax in order to enhance the integration of corporations and individuals, the introduction of Value Added Tax (vat) in order to raise indirect tax collection, and the introduction of a scheme of income tax levied in a global scheme for both individuals and corporations, which includes all kinds of realized income, among others.2 These reforms helped the state to achieve macroeconomic stability and lower inflation (Alvarez, 2007: 7). However, the tax system is still far from providing the Mexican state with enough non-oil revenues to fulfil its functions, and in relation to the gdp it is around 4.5 points below the average of Latin America for both indirect and direct taxes and 25 points below Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (oecd) countries.3

The main reasons for this have been the following. First, the influence of the international and local private sector, which had greater participation in areas previously reserved for state-owned enterprises, to which the state "grants extensive tax preferential treatment, currently accounting for about half of tax revenue" (Alvarez, 2009: 18). After the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (nafta), there has been a focus on fostering the growth of the manufacturing sector as the main strategy for generating employment. Therefore, corporate income tax reductions and duty free vat exemptions on imports of machinery, equipment, parts and material have been granted in order to "set a competitive level against trading partners: usa and Canada" and China (Alvarez, 2007: 6-8).

Second, under the fcns arrangement, the federal government collects around 90% of the total government revenue, which leaves the state and municipal governments in uncertainty about the budget that they are going to receive the following year.4 Also, this highly centralized scheme has favoured the construction of an informal scheme of negotiation between the sub-national and federal authorities, where the political criteria affect the allocation of the resources (Cabrero & Zabaleta, 2011:372). Politicians under strong political competition direct more resources to those regions with high voter turnout, or leave segments of the population untaxed. Moreover, the federal government has focused on trying to decentralize the pull of federal revenue collection without helping or encouraging states and municipalities to improve their institutional capacities first. For instance, in 2004 state governments were empowered to tax individual income obtained from professional services, leases of fixed property, disposal of property, and business activity. Nevertheless, "by 2006 only three state governments - Chihuahua, Guanajuato, and Oaxaca - had already implemented some form of local cellular tax" (Alvarez, 2007: 20).

As a result, the Mexican state has been unable to mobilize enough resources towards social needs and the generation of employment despite the fact that public expenditure has increased in recent years. Therefore, the state has had to implement a residual welfare model directed only at the poorest, who have to be involved in participating in the solution to their own problems. Moreover, due to its weakly institutionalized bureaucratic apparatus, the state has been unable to find sectors in which it could have a competitive advantage and this has impeded employment generation.5

The bureaucratic or civil service reform, on the other hand, was part of the second generation reforms, which included governance considerations mainly pushed by the World Bank. This reform was considered to be one of the most important in the history of the country for scholars, researchers, politicians and society in general (Méndez, 2004; Merino, 2004), since it "aimed for the first time at introducing merit as the guiding principle for selecting personnel policies across the federal government agencies" 77 (Dussauge, 2011: 53). The law sought to establish "a mechanism for guaranteeing equal opportunity of access to the public administration based on merit and with the goal of advancing the development of public administration for the benefit of society" (Article 2, lspc - Ley del Servicio Profesional de Carrera en la Administración Pública Federal 2003 in Spanish, my translation).

However, the patronage and clientelist legacies and issues with the design and implementation of the civil service have constrained the development of an effective bureaucratic apparatus.

The key point that allowed the implementation of the civil service was the implementation of electoral democracy in the early 1990s (Panizza & Philip, 2005:690). The public sector reforms in Mexico were always restricted to some degree by the pri political party, whose officials used the resources of the state to reward party members and party activists for political support rather than to represent the interests of society. When Vicente Fox took over in 2000 representing the right-wing political party Partido Acción Nacional (pan), reform of the civil service was made one of the main priorities of the government. The civil service reform was part of the 2000-2006 Presidential Agenda of Good Government, which aimed at building institutions for markets. However, reformers had to use "non 'market- reform' arguments such as the consolidation of democracy and the reconstruction of state capabilities" (Panizza & Philip, 2005: 691), in order to prevent people from associating the reform with the negative effects of the first generation reforms, finally enacting the Federal Public Service Career Law in 2003.

The new law only applied to around 40 000 workers at the federal level, leaving aside the unionized officials and those who work in offices where the state and the private sector share control. Therefore, it is a limited law if we take into account the fact that the number of civil employees of the whole Federal Public Administration is more than 1 500 000, (Grindle, 2010:15). Moreover, the traditional appointing methods are still used; the governmental officers have found gaps in the law to keep appointing positions. Dussauge found that many workers are appointed using Article 34 of the lspc, which "was originally introduced to allow for non-competitive, temporary appointments, needed in case of emergencies and other exceptional circumstances" (Dussauge, 2011: 62). In 2007, Felipe Calderón (2006-2012) brought in changes with the aim of improving the effectiveness of the law. In particular, he "provided additional requirements for using Article 34 of the lspc-2003, in order to limit the number of non-competitive appointments that were apparently being made for partisan reasons in most cases" (Dussauge, 2011: 67).

However, he opened a window to patronage and clientelism by leaving every ministry in charge of the implementation of lspc without clear rules of inspection, constraining the development of an effective bureaucratic apparatus.

In the local governments the situation was even worse. For instance, in the case of the states by 2008, only eleven out of the 32 had introduced a lspc.6 However, even in the states that have civil system laws, the same patronclient legacies that impede the development of an effective bureaucratic apparatus at the federal level do the same at the state level.

Moreover, despite the fact that most of the public servants hold bachelor degrees and have some experience, their human resource systems lack the technical and organizational expertise to put it into operation (Martínez, 2008:213-214).

The situation of the municipalities is the worst of the three levels of government. Cabrero and Zabaleta found that most of the municipalities in Mexico, even the urban and metropolitan ones, lack important basic rules and norms such as those that regulate basic aspects of the political structure or those of citizen participation in the activities of the municipalities. Moreover, most of the municipalities still lack civil service systems that provide corporate coherence and allow the public servants to gain experience as well. This, in consequence, brings about feeble intergovernmental relations between the different levels of government (2011: 378-391).

By the early 2000s, the goals of the structural reforms had been accomplished, having been successful in lowering inflation, reducing fiscal deficits and to some extent income inequality as well. According to Handelman, in Mexico economic growth was also stimulated for the first time since the Mexican miracle (Handelman, 1997: 127). However, poverty rose inexorably during this period since the openness of the economy profoundly changed the governance of labour markets in middle-income countries where there was a relaxation of traditional employment protection, such as occupational welfare, job security and severance pay, bringing about a blurring of the division between the formal and informal sectors since employment shifts became more frequent and volatile (Haagh & Cook, 2005: 171-172). This, along with the decline in the quality of public services such as education and health care due to the cuts in public spending, has seriously aggravated the situation of the middle and lower classes, especially the poor in urban areas, since the industrialization of the stabilizing period had transformed the country's society from a rural to an urban context (around 75% of the whole population) (Moreno-Brid, Pardinas and Ros, 2009:157).

The Brazilian experience with the ccts

The consequences of the structural reforms put pressure on Latin American leaders to find ways to tackle inequality and poverty. The introduction in the early 1990s of the ccts was one of the main responses to these pressures, especially in Latin American countries, which have some of the highest levels of inequality in the world. In the last two decades, this programme has been used as one of the main poverty alleviation strategies all over the continent; Brazil has Bolsa Familia, there is Chile Solidario in Chile, Colombia has its Familias en Acción programme (fa), Ecuador Bono de Desarrollo Humano, Honduras the Programa de Asignación Familiar (praf), Jamaica the Programme of Advancement through Health and Education (path), and Nicaragua the Red de Protección Social (rps).

Bolsa Familia was the flagship of the Brazilian Workers' Party and was created under the command of Luiz Ignacio Lula da Silva (2003- 2006). The main goal of the programme was to break the intergenerational cycle of poverty by helping the poor to acquire capabilities that would 79 improve their chances of obtaining a sustained income in the labour market.7 In Bolsa Familia, Da Silva centralized the programmes of direct assistance that already existed and expanded the coverage quite quickly; by 2006 it was already covering 11.2 million families, becoming the biggest cct programme in the world.

In the educational component, the objectives of the programme are, as we shall see later, very similar to those in Progresa-Oportunidades: to increase educational attainment to reduce poverty in the long run, to reduce poverty in the short term with a grant, to reduce child labour and to serve as a safety-net for poor families, preventing them from becoming vulnerable to sudden shocks in the economy. The programme has been successful in achieving most of its objectives; however, its success comes from the strong institutionalization of the labour market, which has been materialized in the reduction in the levels of labour informalization and economic insecurity. According to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (eclac), in Brazil since 2005, the annual employment rates have been higher than the unemployment rates, while in Mexico since 2001, the annual employment rates have been lower than the unemployment rates (2010: 122-123 and 234).

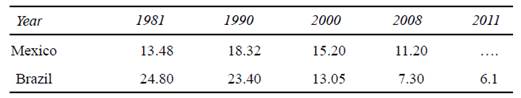

Table 1.1 shows how, in Brazil, extreme poverty has been drastically decreased in the last decade, whereas in Mexico it has been reduced at a slower pace. Unlike the Mexican case, the central factor that shaped the Brazilian labour market response to the liberalization of the economy was the fact that the inception of a democratic regime started first and this was followed by the opening of the economy, which allowed the state to take advantage of its developmental tradition (corporatism) and the collective and social capacities of its unions in order to adjust the institutional framework of the labour markets to the new conditions (Haagh & Cook, 2005: 179). According to De Andrade et al., the main changes introduced were: 1. the expansion and introduction of legal open-ended contracts (temporary work contracts, part-time contracts, and so on); 2. the increase in the state's revenue collection to tackle the growing public debt; 3. the adjustment of institutions that allow a real enforcement of open-ended contracts and the bargaining of employment conditions; 4. the formalization of micro and small enterprises, allowing access to credit and tax incentive programmes, which has contributed to the formalization of employees contracted by small businesses; and 5. the increase in the minimum wage (2010: 8-31).

Source: eclac 2004, 2010 and 2012.

The introduction of ccts in Mexico

Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado (1982-1988) was the president who started the implementation of the pro-market structural reforms. However, it was Salinas who consolidated them. Seeking to revive the confidence of Mexico's citizens after the poor results of the Washington Consensus reforms, he launched Pronasol (National Solidarity Programme in English), a compensatory or means-tested programme whose main objective was to reduce poverty, creating social funds as targeted safety-nets for the poorest who did not have income-earning capacities (Székely & Fuentes, 2002: 131), along with measures that would encourage their participation as a condition for obtaining benefits (Piester, 1997: 469). The programme included food support aid, credits to farmers, grants and scholarships for children, building and refurbishing public schools, communal electrification, and other similar measures.

However, the programme was criticized as being corrupt and clientelist, and it was used more as a political tool for electoral purposes than as an effective poverty-reduction programme (Molinar and Weldon, 1994: 136).

Under Salinas, gdp recovered, growing 2.0% annually; however, income inequality and urban poverty kept on growing. Ernesto Zedillo therefore inherited a serious political and monetary crisis. In this context, a new means-tested programme was launched with the intention of raising the human capital of the extreme poor through the provision of cash conditional upon a change in their behaviour as a way to alleviate poverty. In 1997, Zedillo announced the start of Progresa (an Education, Health and Nutrition Programme) supplanting Pronasol, a programme with similar goals but more concerned with the causes rather than the consequences of poverty. The programme provided a cash transfer delivered every two months to extremely poor families conditional upon the school attendance of their children, who had to be enrolled between the third grade of primary school and the third grade of secondary school, and health checks for the whole family, especially pregnant and nursing women, on a regular basis. The general idea behind the programme was to provide a minimum income to the poorest so that they could invest it in the education and health of their children who, once educated and healthy, would acquire capabilities that would enable them to keep on obtaining an income in the labour market in the mid and long-term to move out of poverty by their own efforts (Levy, 1991: 44-55).

Accordingly, Progresa was first directed at rural areas, where the incidence of poverty was higher at that time, and using a well-supported criterion to identify the right families and avoid clientelism the targeting methodology comprised three phases: 1. zones were selected according to the marginality index of the National Council of Population (conapo) and the availability of education and health centres was a prerequisite for the operation of the programme in order to encourage the state and municipalities to invest in social development; 2. households were assessed by a survey which, using statistical methods, would determine whether the household was poor or not; and 3. the final list of families integrated into the programme was presented to representatives of the community for revision. In addition, in order to empower women and change their role within society, the cash transfer was 81 given to the mother of the household, and in order to encourage girls to stay in school, after elementary school the amount of the cash transfer was higher for them than for boys.

When Progresa was launched in 1997, it covered around 300 000 families in rural areas of twelve states. By the end of Zedillo's term of office, it covered almost 2 500 000 families living in marginal rural areas all over the country. The early evaluations of Progresa demonstrated significant impacts on the wellbeing of the recipients, such as increasing school attendance and improving health outcomes (Adato, 2000; Behrman & Hoddinott, 2000; Parker & Skoufias, 2000). Due to the good initial results of the programme, Vicente Fox (2000-2006) not only maintained the programme but also expanded it. Nowadays, the programme, re-named Oportunidades in 2002, covers more than 6 000 000 families, in both rural and urban areas.

Fox took over in 2000 representing the right political wing pan, after 70 years of the hegemony of the pri, in a stable political, economic and social context. This takeover by the right-wing party, however, is far from being the consolidation of democracy in Mexico. According to Bayón, the course of action of the National Action Party is in line with the Washington Consensus (Bayón, 2009: 2). The main changes that the programme incorporated were the coverage of urban areas, grants to students in high school, a pension for elderly people and an official definition of poverty. Following Amartya Sen´s distinction between absolute and relative poverty (Anand & Sen, 1997: 4), it was argued that the former is the deprivation of basic capabilities to subsist (nourishment and health) and the latter is the lack of adequate means in a specific society to achieve those capabilities (sedesol, 2002: 19).

Felipe Calderón Hinojosa (2006-2012), also from the right-wing political party, did not inherit any kind of crisis. However, when he faced the food crisis in 2007-2008 and the financial crisis in 2008-2009, he not only continued spending on social programmes and maintained Oportunidades, but also expanded the programme making three main additions that were part of a strategy which he labelled: Vivir Mejor ('To Live Better'): 1. children from birth to nine years old were included in the programme; 2. the creation of the Living Better Fairs (Ferias Vivir Mejor in Spanish) with the purpose of letting the ex-recipients know about the options for study that exist so that they keep studying when they have finished high school and; 3. the creation of the website Vas con Oportunidades ('Go ahead with Oportunidades', in English) with the purpose of giving information to the ex-recipients about ways to finance further study, such as scholarships or grants or information about the labour market policies offered by the federal government to society in general.8

As we have seen, the programme has kept growing; however, it is still financed from the oil profits and loans from international institutions of development due to the weakness of the fiscal institutions. In 2008, for example, the Inter-American Development Bank approved a loan of $2 billion to expand the programme and in 2013 approved another loan of $600,000,000.9 Moreover, the recipients have many responsibilities to fulfil in order to receive the benefits;10 however, even though the recipients fulfil their responsibilities they do not have access to employment, which is the main goal of the programme.

Methodology

Our methodology was a mixture of quantitative and qualitative methods and can be divided into four main parts.11 The first part was the focus group technique, by which we interviewed one small group of ex-recipients (eight of them), consisting of young people who were between eighteen and twenty-three years old and who had already completed high school, in order to understand their lives and define the kind of questions we would like to ask about their perceptions and experiences of the constraints they face in obtaining sustained income in the labour market in relation to the institutional capacities of the state. In order to analyse the data obtained from these interviews, we transcribed and coded them in relation to our research objectives.This preliminary interview allowed us not only to understand the lives of the ex-recipients but also put us in an excellent position to locate other relevant actors (in the government, the private sector and civil society) with whom we could also conduct qualitative semi-structured interviews in order to triangulate the findings from the focus groups.12

The second part was nineteen semi-structured interviews that we undertook with different actors of the social structure involved in our research problem, such as government officials, private sector employers and civil society organizations.13

The third part was the analysis of several 83 types of official documents related to the institutional capacities of the Mexican state, mainly requested through the websites of ifai (Federal Institute of Access to Information and data protection, in English) and infoem (Institute of transparency, access to public information and protection of personal data of the State of Mexico and Municipalities, in English). Once we had completed the qualitative interviews and the data analysis from secondary resources we proceeded with the development of a questionnaire and the building of the sample to which we applied it.

We applied the survey to ex-recipients of the Oportunidades programme of an urban municipality of the State of Mexico called Toluca in early 2012. We chose the State of Mexico because it provided us with important conditions to present a good example of the extent to which the weakness of the institutional capacities of the state impedes the achievement of the main goal of Oportunidades in urban zones. That is, there is: 1. a labour market with a large service sector; 2. a large variety of small, medium and large industrial business; and 3. a representative percentage of ex-recipients of the Oportunidades programme who had completed the high school level.14 We next had to choose the specific municipality, we decided to choose Toluca since it is the capital of the State of Mexico, where the local executive, legislative and judicial powers reside (of both state and municipality), which gave us a sense of unity at the local level, allowing us to show the extent to which the weakness of the institutional capacities of the state impedes the achievement of the main goal of the Oportunidades programme.15 In sum, in Toluca we found a high level of industrialization and a large number of people working in the service sector, especially in small businesses, and there was the presence of the state in its three levels of government. If the programme worked, it should be there.

The survey was applied to 352 ex-recipients of the Oportunidades programme who had completed high school while they were members of the programme and who were between eighteen and twenty three years old, and of these 209 (59.4%) were female and 143 (40.6%) were male.16 At the time that we applied the survey, the whole population that we interviewed resided in Toluca, (195) 55.4% of our population were working or had a job or an occupation, (95) 27% were studying for a Bachelor degree (BA) and (62) 17.6% of the population were unemployed.17 Out of the 100% of our population who had a job or an occupation, (123) 63% of them were working in the service sector, around (43) 22% were working in the industrial sector and (29) 15% had a business of some kind.18

Mexican labour mark ets and their informal flexibility

The main advantage of our perspective on the institutional capacities of the state and their interaction with the welfare system is that it helps us to shed light in more detail on some of the specific causes of the disappointing adjustment of the labour markets to the openness of the economy during the 1980s than previous explanations (see Schneider & Karcher, 2010). As for the role of the Mexican state in that regard, we argue that the main issue is the weakness of its institutional capacities, which have brought about an increase in the levels of labour informalization and economic insecurity. More specifically, the weakness of the regulatory-market capacity of the state has brought about less employment protection, triggering short job tenure, which, joined with the weakness of the fiscal capacity of the state that constrains the effective provision of basic services such as education, impede the citizens from obtaining sustained income in the labour market, as we shall see next.

Weak enforcement of the labour regulations

The Mexican labour market model of the post-war period was the result of the process of the integration of the different social groups to maintain social stability and at the same time to provide the labour institutional environment of a capitalist system. It was a top-down process that was materialized in Article 123 of the Mexican Constitution and the Federal Law of Employment (LFT - Ley Federal del Trabajo, in Spanish). According to Bensusam, the enactment of the ltf in 1931 and the new law of 1970 were to counterbalance Article 123 of the constitution, which gave occupational rights to the people without taking into account the bgs and the mncs, harming their interests.

This, added to the 1929 crisis, forced the state to enact a law that protected the interests of the private sector, expanding the limits of the discretion of the state to intervene in the conflict between labour and capital both in times of growth and stability and in times of economic crisis (2006: 137). It was thought that with the lft and a system of labour justice that worked under the executive branch without formal ties to judicial power, the control of the different actors of the social structure would bring about social stability, allowing economic growth to be achieved. The reality was that the state controlled the private sector and civil society through corporatist and clientelist relationships, channeling their demands into personal relationships, which limited the expansion of universal social rights.

During the 1980s, the 1990s, and the first decade of the 2000s, the Mexican labour markets did not have any changes in their institutions despite the enormous transformation that the structural reforms brought about and electoral democracy (Bayón, 2009: 307). Nonetheless, after the openness of the economy, combined with the clientelist legacies of the Mexican state, the bargaining power of the private sector (national and international) grew so much that it escaped the control of the state, influencing the adjustment of the labour market institutions informally in their own interest without going through a formal process. These groups have influenced the disappearance of social protection, bringing about high levels of labour informalization and economic insecurity, where the poor are the most affected.19

This is a paradox because the reach of Mexican labour legislation is quite wide since it includes every waged worker from both the formal and the informal sectors without the need for a formal contract (Bensusam, 2006: 321).

Moreover, Articles 35, 36 and 37 of the Federal Labour Law establish that all labour relations, except for those covered by temporary contracts and contracts for a specified job, are indefinite and even despite the fact that there is no written contract, the workers should still receive the same rights because the responsibility for the lack of a formal contract lies with the employer and not the employee. However, due to the weak enforcement of the labour regulations, not complying with labour regulations in Mexico implies a low cost, which has been utilized by the private sector not only to avoid investing in organizing labour but they have also pushed the shrinking of unions in order to have leeway to adjust the labour market to their benefit since unions are the only force that could counterbalance the power of the private sector in relation to the workers´ rights and working conditions.

For instance, at the federal level, despite the fact that in 2003-2004 a civil service system that was supposed to bring about higher organizational capacity, professionalization and corporate coherence was implemented, the corporatist practices that structure the institutional framework of the state have constrained the development of an effective labour inspection apparatus. At the federal level, the coverage of inspectors (776 by 2012, all of whom are part of the civil service system of the Federal Public Administration) per worker (around 50,000 workers) was very low in comparison with some other developing countries (Romero, 2008:130). Moreover, there are two kinds of inspector: 1. specialized inspectors, in charge of watching the businesses that are considered to be high risk, such as chemical companies; and 2. regular inspectors, in charge of watching low-risk companies.20 In their respective jurisdictions, both are responsible for the enforcement of all the labour norms and regulations. The problem is that although they are recruited according to their "merit", they are not specialized in the different industrial sectors.

The profiles that they mainly look for are lawyers and engineers. However, the training courses that both of them receive are only about the labour norms and regulations and interpersonal relationships and they are not trained in the particularities of the production processes of the different sectors of the economy.

In addition, supervision at the federal level comprises only the verification of short-term goals and the procedure to change them is very rigid. In consequence, there is no way to establish remedial plans that take into account both legal and economic variables in the medium and long term. This hinders them when it comes to understanding the obstacles that prevent firms from complying with the law and proposing legal and/or technical solutions adapted to their needs, which, along with their low wages, lack of experience and necessary equipment to perform inspections properly, makes it difficult to detect irregularities.

The situation in the State of Mexico, where we undertook the survey to the ex-recipients of the Oportunidades programme, is not very different from what we have presented about the federal level. By 2012 there were only 27 inspectors in the State of Mexico, 80% of them politically appointed.21 Of those, twelve were in charge of monitoring health and security issues with a goal to inspect 150 enterprises annually (around 6200 workers) and fifteen were in charge of monitoring general conditions of work and training issues with an annual goal of 300 enterprises (around 11,500 workers).22

Moreover, due to the lack of budget and staff, 87 they do not have access to an updated census of centres of work, which forces them to limit inspections to the companies for which they have all the information. Therefore, informal enterprises, those that do not pay taxes whatsoever, are outside the scope of the inspection because they are only inspected if a worker makes a complaint. Moreover, the lack of institutional coordination with the Federal Ministry of the Treasury (Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público- SHCP) makes it even more difficult since the average period of life of a business or enterprise in the service sector is normally two years, but the two ministries do not share information that could help to keep the census updated.

On the other hand, at the federal and state levels, the main organizations in charge of labour justice are the federal and state Boards of Conciliation and Arbitration (jfcya - Junta Federal de Conciliación y Arbitraje and jlcya - Junta Local de Conciliación y Arbitraje in Spanish). They are in charge of the resolution of labour disputes that arise between workers and employers, or only among employers or among workers in the economic sectors of their jurisdiction. These boards are structured into a tripartite scheme in order to ensure "equal" representation between the private sector and workers: an equal number of employers' and workers' representatives and a representative of the government, who plays the role of a referee to defend workers' rights. However, in spite of being the organizations in charge of enforcing labour justice, they do not belong to the judicial power but they are supposed to be autonomous bodies. Moreover, the representatives of the state in both its federal and local offices are appointed directly by the federal and state executive power, respectively. Furthermore, Article 919 of the lft states that these Boards can modify agreed working conditions (in collective contracts) in order to achieve balance and social justice in the relations between workers and employers. In this sense, there is a major contradiction in the law as far as the performance of the bureaucratic apparatus of the state is concerned since the Boards should not be playing both roles.

Weak labour unions

During the post-war period, the relationship between the government and the unions was always based on corporatist arrangements. In order to make sure that the state could control the formation and activities of the unions, it was established that unions needed authorization from the state to be established and that the employer could hire only those employees who belonged to the union that the company or firm chose to work with. Consequently, the most powerful unions were in key areas such as education, the oil industry and health care and their leaders frequently received benefits from their relationship with the government, such as seats in the government in exchange for electoral support. However, the unions had power to bargain with the firms and with the government since some of their members had access to high positions in the government and also because after 40 years of working with the government representing the interests of workers they had built collective capacities that allowed them to escape from the control of state officials.

The structural reforms of the 1980s reversed and worsened that situation. In order to attract international capital, the government offered cheap and controlled labour (Hathaway, 2000: 10), bringing about a considerable decrease in union membership; the percentage of the workforce which was unionized went from just over 30% in 1984 to under 20% in 2000, and to 10% in 2009, and in the micro-enterprises it is practically non-existent (Ruiz, 2009: 178), and the same corporatist practices of the past have been used to keep the few empowered unions left, such as the education union, under control. Among the ex-recipients whom we interviewed, only 7.1% of them had access to workers' organizations, 45.2% did not and 47.7% did not answer. The enterprises that belong to the service sector present perhaps the worst scenario since out of 100% ex-recipients who were working in that sector in an established business, only 11% had access to worker organizations. As far as the manufacturing sector is concerned, only one third (14) of the ex-recipients (43) had access to workers' organizations.

In consequence, the credibility of the government-allied unions has changed radically since unions are no longer capable of delivering customary benefits to their members, bringing about discrepancies between the main workers' organizations (Bensusam & Middlebrook, 2012: 74). For instance, since the late 1970s onwards when the restrictive wage policy to avoid inflation was established as part of the structural reforms between the unions, the state and the private sector, labour representation in the federal chamber of deputies and the purchasing power of the minimum wage have decreased simultaneously (Bensusam, 2008: 31). The limited access to organizations that represent workers' interests, reinforced by and complemented with the weak law enforcement of the organizations in charge of applying labour justice, has impeded the state from harnessing private sector interests into areas of general interest. Therefore, the private sector has found it relatively easy to flexibilize the labour market institutions, which, has increased the levels of informalization bringing about short job tenure and income insecurity.

Short job tenure

Due to the weakness of the unions and the failure of the state to enforce labour norms and regulations, labour mobility has relentlessly increased. Levy argued that in 2006 18.5 million economically active people remained in the same job for less than five years (Levy, 2007: 7). Moreover, by June 2009 the number of formal full-time and temporary workers registered with the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (Mexican Institute of Social Insurance - imss) had declined by 596,200 compared with a year earlier (ILO, 2010: 1). The ways in which the private sector takes advantage of the labour justice system in Mexico vary; enterprises such as Wal-Mart and Office Max, for instance, treat their employees as associates and not as employees in order to avoid paying taxes and contributions from which social security is normally financed (Ruiz, 2009: 175).

However, the main gap that they have found is outsourcing, which is used to reduce costs and eliminate job duties but mainly to avoid distributing the share of the profits that workers deserve, even though the employment law specifies that whoever uses outsourcing to reduce labour rights will face high fines.

There are two kinds of outsourcing: 1) labour outsourcing, where a company or firm that needs to have some work done resorts to an intermediary to hire workers to have it done;23 and 2) outsourcing of goods and services, where a company or firm entrusts to another the provision of goods and services and the latter undertakes to carry out the work at its own risk, with its own financial, material and human resources (Ermida & Orsatti, 2009: 20).

The companies that outsource, normally big or medium sized companies, are forced to be fully responsible for the health and safety issues of the workers that the medium company utilizes, but all they do is to put a clause in the contract stating that the small company will register the personnel that the medium company uses to provide the service or good with imss (although this does not necessarily always happen), and with this formula they do not have any other duty to the employees of the medium or small company. Small companies, then, normally through an intermediary, outsource the personnel that they need to have the work done, hiring them on temporary (probationary and initial training) contracts.

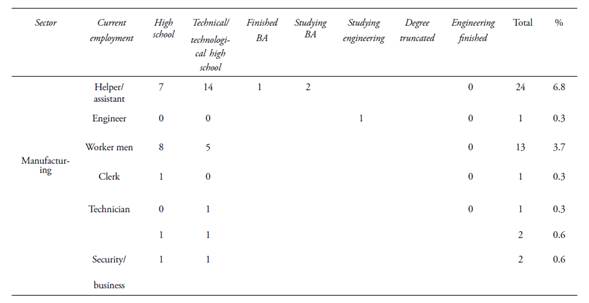

As an instance, most of the jobs of the exrecipients who we interviewed were not only low-qualified ones, as Table 1.2 shows, but also most of them had temporary or informal contracts, which put them in danger of falling into poverty again since by 2012, there was only one federal entity all over the country, Mexico City, which gives access for workers to unemployment insurance and, as we shall see in the next sections, training and access to credit is scarce or limited. As a result, there is a very high level of labour mobility since workers are always changing jobs either because their contracts expire or because they are looking for something better paid and more stable. Out of the 100% ex-recipients whom we interviewed, only 7.4% (26) had jobs with a formal stable contract, 20.5% (72) had jobs or occupations without written contracts, 17.4% (61) had temporary formal jobs, 17.6% (62 were unemployed) and the remaining 37.2% (131, mainly students) did not answer. Therefore the income of those without written contracts, those with temporary contracts, the unemployed and the micro-entrepreneurs (more than 60%) was unstable.24 The sector that offered most of the formal contracts was the service sector. However, this is the sector where most of the ex-recipients without a written contract work as well.

Accordingly, when we asked the exrecipients what was the most worrying issue about their working conditions, the majority of them (29.3%) answered that it was their unstable salary, especially those who were working in manufacturing where, as argued before, most of these enterprises are outsourced by bigger enterprises. The second most important worrying issue that they signalled was that there is no employment at all (20.7%).

On the other hand, almost half of the exrecipients whom we interviewed have had at least between one and three jobs since they finished high school when they were eighteen years old, and as they grow older the number of jobs that they have had grows, like the 23-year-olds, most of whom have had between four and six jobs. This context, on the one hand, disincentivizes workers from investing in acquiring specific skills since they are not certain whether they will keep their jobs in the long run. On the other hand, it also impedes them from organizing labour since workers stay in their posts for very short periods of time.

Low skill levels

As explained earlier, as part of the Washington Consensus reforms, the Mexican and Latin American states undertook a process of fiscal decentralization (tax and social spending) during the late 1980s and early 1990s with the intention of both reducing the size of the state and its intervention in the economy, and of improving the effectiveness of the allocation of resources. However, according to Teichman, despite some shift toward social spending to benefit the lower classes in the last few decades, social spending is in general regressive, meaning that it does relatively little to mitigate inequality and poverty (Teichman, 2012: 160-163). Furthermore, in the case of the public education service, which does show some progressivity (in the primary and secondary levels), the service is of low quality, meaning that every time it is more likely that only the lower classes make use of the service whilst the middle and upper-middle classes prefer private education (Teichman, 2012: 160-163).

Accordingly, the main achievements of the programme in this component have been the high enrolment and attendance of children (especially girls) in primary and secondary schools (Scott, 2009: 19). However, although school attendance has increased in recent years, the gap between the poorest and the richest has widened, especially in high school and upper levels, which are the most important in terms of integration into the labour markets in an adverse context of slow growth-employment such as in Mexico (Bayón, 2009: 309-310). A likely reason for this is the fact that the decentralization reform did not cover higher education bringing about regressive and discretionary social spending, being one of the main impediments that the ex-recipients face when it comes to obtaining sustained income in the labour market.

The lack of clear rules for the allocation of resources for higher education has resulted in universities carrying out a discretional negotiation with the federation and the states. This has meant that sometimes investment in higher education is used politically to benefit some of the states that are governed by the same political party as the federal government, especially because students at university level are at the minimum age to vote (Hernández, 2005: 45). The Mexican federal income law requires the publication of the results of a study of the incidence of spending and taxes. According to the results of the publication for 2010, although total spending on education was mildly progressive, that is, it was mainly used by low-income people rather than highincome people, spending on high school education was neutral in urban zones and only progressive in rural areas. At the level of technical education, the concentration ratio 91 showed a regressive national expenditure, and it was progressive only in rural areas. On the other hand, spending on higher education was regressive in both urban and rural areas, and 62.8% of total expenditure was concentrated in 20% of the population with higher incomes (SHPC, 2012: 41).

Moreover, in 1993, the state gave private and public institutions equal access to state subsidies for higher education and authorized public universities to charge students for tuition. As a result, most of the high schools and universities in the country are private schools (Brunner et al., 2008: 18), which puts the poor in a very weak position to compete against the general population for the few places in the public universities. When we asked the ex-recipients 'What is the main constraint that has hampered you from obtaining sustained employment', among the 180 (51%) exrecipients who did not have a contract, were unemployed or had a temporary contract but no access to social security, the most recurrent answer was that there were no jobs at all (69), whereas the second most recurrent answers were the lack of experience (41) and the lack of a ba (41). Only very few of them mentioned the lack of training or maternity leave and even the self-employed answered accordingly, admitting that they had to employ themselves as a result of these constraints.

Source: Author with information from our survey.

In this sense, it would be more important for poverty alleviation to have an employment generation strategy since access to the upper levels of education is not the only constraint. Despite the fact that the internationalization of education is an important strategy of the Mexican state, according to the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) of 2012, which evaluates how educational systems prepare students for life in a larger context, the average Mexican student is one of the worst performers in Latin America. Furthermore, the evaluations have also indicated that "high schools and universities in Mexico have, at best, very weak ties with the productive sector in general and with industry, in particular" (Brunner et al., 2008: 50).

Moreover, along with the survey that we applied to the ex-recipients of Oportunidades, we also had the opportunity to interview a member of an automotive cluster who worked in the State of Mexico between 2008 and 2010

The cluster was an initiative of the government 93 of the State of Mexico in order to encourage the growth of the automotive industry, one of the most important industries in the State of Mexico, and generate employment. The idea was to gather the big, medium, small and microenterprises and other actors that are part of the automotive sector, link them to each other and listen to them, and then come up with solutions that benefit everyone. When we asked him about the constraints that the members of the cluster, especially the private sector, had found in relation to the correlation between the skills of the labour available for hire and what the firms needed, he commented that it was so weak that a high investment to train every worker that the firms hire is unavoidable. According to him, on average, every one of the three automotive firms (mncs) that were part of the cluster spent around 2000 dollars on every worker to have them trained. He also stated that, in an effort to improve this situation, the universities that are situated in the State of Mexico had been invited to join the cluster. However, and despite the fact that the universities' representatives were very committed to helping, nothing could be done because the design of the programmes is the responsibility of the Federal Ministry of Education.

As can be seen, the regressiveness of public spending impedes the ex-recipients of the Oportunidades programme from accessing the educational levels that would allow them to increase their capabilities to obtain sustained income in the labour market. Moreover, as far as the Oportunidades programme's goal is concerned, the weak correlation between the skills acquired through the education received through the programme and those needed by the private firms is perhaps the main impediment to the ex-recipients obtaining a sustained income in the labour market as far as education is concerned. An important question then is what is the state doing to help those poor who cannot keep studying and/or those who are unemployed to obtain sustained income in the labour market?

Informal sector

According to Maloney, the informal sector in Latin America is the analogue of the entrepreneurial small firm sector found in developed countries (Maloney, 2004: 1165). As a matter of fact, Canales and Nanda noted that smes represent more than 99% of all Mexican firms. They have accounted for more than 70% of all employment since 1993, and they generate more than 50% of gdp (Canales y Nanda, 2008: 63).The difference is that in Latin America workers are forced to work informally, relying on family networks to cover their social protection (Temkin, 2009: 50), due to the circumstances that we reviewed in the previous sections.

In line with the Washington Consensus reforms, the Mexican and Latin American states have implemented different self-employment policies as the main labour market policy to solve the market failure of unemployment.25

These policies are supposed to alleviate the unemployment resulting from the necessary reforms and initiatives meant to restructure the economy and institutions of government for a trade-liberalized world (Tendler, 2002: 3). Two important points of that strategy is to lower taxes and to open access to finance to encourage citizens to set up their own business since it is believed that high taxes and the lack of finance inhibit entrepreneurialism and/or force business to remain informal (Tendler, 2002: 4-5).

However, most of the ex-recipients whom we interviewed (90.6%) were not interested in having a business as a way of life and only 9.4% had considered it. Moreover, there is no evidence that these programmes contribute to the creation of new enterprises, but only the strengthening of the existing ones (unam, 2009: 3). Tendler argued that in Brazil, to some extent, the success of these policies is due to the fact that the state has been able to engage effectively with micro-entrepreneurs forming clusters to help them increase their wholesale and retail trade but at the same time taxing them to increase the possibilities of formalizing them (2002: 8-10). In Mexico, on the other hand, the formation of groups to receive the finance does not have the goal of forming clusters to bring them closer to bigger enterprises but to make sure that the borrowers will pay the money back on time, since people do not necessarily have to belong to the same sector of the economy or work on the same activity or occupation. Most importantly, most of the micro-enterprises in Mexico are informal and the main difficulty in approaching them to formalize and help them to finance their business is that people do not see benefits or incentives to paying taxes, which decreases their opportunities to survive in the long-run.

When we asked the ex-recipients in question 31 about the level of trust that they had in relation to the way Mexican officials use the taxes that they have paid, 76.4% answered very low or low, 2.3% answered average and the remaining 21.3% answered high or very high.

In this context, Levy claimed that direct assistance programmes such as Oportunidades could act as an incentive to work informally since, trying to maximize their gains, people would prefer to stay in the informal sector, where they are independent and have help from the government, which limits economic growth (Levy, 2007: 30). However, and in the light of the information presented above, we agree with Escobar and González, who argued that this view could be mistaken because the cost of informal social protection could be higher and because relatives are not always in a position to help their family. They found that those workers who leave the formal sector in order to set up a business in the informal sector to achieve independence or for financial reasons even keep paying a fee to the imss or the Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado (Institute of Security and Social Services of the state's workers - issste) in order to guarantee their access to a pension (Escobar y González, 2008: 39). Moreover, if we were to say that direct assistance hampers productivity, then any kind of assistance from the government would be harmful too, and the lesson that we have learned reviewing the Mexican case is that the lack of direct assistance has been more harmful, especially for the poor. As a matter of fact, when we asked the ex-recipients in our question 32 'If you had to choose between a job with access to health security although some deductions were made from your salary or wage, or a job in which you received your full salary or wage 95 but without access to health services, what would you prefer?', 73% of the ex-recipients answered that they would prefer to have a job with access to health services rather than a job without it, even though they would not receive their full salary.

The point on which both Levy (2007), and Escobar and González (2008), agree is that if productivity and employment are not raised, perverse incentives might be created, impeding economic growth. Cárdenas claimed that what informal firms lack is help to upgrade their production (Cárdenas, 2009: 278), which also decreases tax collection and with this the assistance that can be provided to the poor. Furthermore, Moreno-Brid, Pardinas and Ros argued that Mexico's growth strategy "has failed to create the number of jobs required by the labour force estimated at between 800,000 and one million per year" (2009: 155) and according to Peralta, the average annual generation of necessary jobs for 2008-2030 is 641,500 per year, and even if gdp grows at 7%, it will not be possible to abolish unemployment until 2030 (2004: 1460).

Conclusions

We briefly discussed how the economic model of the Mexican state before the implementation of the structural reforms of the 1980s seemed to be more socially inclusive than in the last three decades, particularly due to the extensive social rights that were negotiated by the labour movement and thus more conducive to alleviating poverty than the current model. However, the weakness of the institutional - regulatory-market and fiscal - capacities of the Mexican state have contributed importantly to determining the negative outcomes of the development strategies followed before and after the implementation of the structural reforms in the 1980s. The difference between the two periods was mainly the shift in ideology behind the overall development strategy of the state, which brought about the withdrawal of the state from the coordination of the economy and distribution of the services in the latter period, which exacerbated even more the socio-economic inequalities of the population.

The crisis of the 1980s implanted the belief that what was needed to solve the institutional problems of the state was to reduce its size and implement a market-led development. In this context, the Mexican state prioritized macroeconomic stability and the control of inflation, embarking on an export-growth strategy, and making deep cuts in public spending following the minimalistic view of a welfare system that serves only as a safety net where the market fails, bringing about the exacerbation of socio-economic inequalities and poverty. In recent years, social spending has been increased in order to alleviate these negative consequences. Paradoxically, however, the still weak institutional capacities of the Mexican state have not only brought about less employment protection but also they have impeded employment generation, in this way, constraining the alleviation of poverty.

First, the weakly institutionalized bureaucratic apparatus to monitor and apply labour justice to make employers comply with the law, helping them at the same time to increase or maintain their productivity to foster employment growth brought about a The experience of the Mexican state with the conditional cash transfer programmes to alleviate poverty modus operandi within the enterprises by which they started to flexibilize, informally, the labour market institutions. Second, the limited access to workers' organizations that provide third-party enforcement in the world of labour constrains workers from exercising their political rights and in consequence the achievement of social rights. On the other hand, there is no third party enforcement which can bring about a situation in which the different incumbents in the world of labour monitor each other, ensuring that the law is enforced impartially and impersonally. The result of this is an increase in the levels of labour informalization and short job tenure since the enterprises, in order to lower their production costs, offer only short-term contracts with very low salaries and without access to benefits such as training or social security services in most of the cases.

As a matter of fact, in the focus group the ex-recipients argued that, on the one hand, because of corruption law enforcement is normally in favour of the patrons since they can pay for prestigious lawyers to represent or advise them and that is the only way to ensure that the law is applied correctly. On the other hand, the ex-recipients perceived unions to be a tool used by the private sector to organize the workers and make them accept their labour conditions rather that to protect workers' rights. All of which has contributed significantly to employment being institutionalized, informally, as short-tenured with minimal benefits.

In the case of the fiscal capacity, the federal level has kept for itself not only the collection and distribution of fiscal resources but also the policy-making of important services such as education, all of which has brought about a weak correlation between the skills acquired in formal education and those needed in the labour market. Moreover, the federal level has allowed the private sector to step in, and this has brought about a wide educational gap between the rich and the poor since it is difficult for the poor to reach higher education which, according to our results, is the level that could make a difference as far as finding sustained employment is concerned. In point of fact, in the focus group the ex- recipients perceived the (institutional) process for entry to the public universities as non-transparent, which makes them focus on studying at a technical high school rather than planning a career with a ba.

CCTS are designed to enable poor children to attend schools and health centres, allowing them to increase their human capital so that they can obtain sustained income in the labour market in the mid and long-term. Research has confirmed that the programmes have had positive effects in different areas of the wellbeing of the recipients. We have reviewed here some of these positive achievements in the educational component. However, our analysis suggests that the Mexican state will be unlikely to alleviate poverty because the weakness of its institutional capacities impedes the provision of effective training and labour market policies that complement the programme and enable the poor to obtain a sustained income in the mid and long run.

References

1Adato, M. (2000), Final Report: The Impact of Progresa on Community Social Relationships, Washington, D.C., International Food Policy Research Institute.

2. Álvarez, D. (2007), "Tax System and Tax Reforms in Mexico", in Bernardi, L., Barreix, A., Marenzi, A. and Profeta, P. (ed.), Tax Systems and Tax Reforms in Latin America, New York, USA, Routledge.

3. Álvarez, D. (2009), "Tributación directa en América Latina: equidad y desafíos. Estudio del caso México", Documento presentado en el seminario: Tributación, equidad y evasión en América Latina: desafíos y tendencias, Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (cepal), Santiago de Chile, 24 y 25 de noviembre.

4. Anand S. & A. Sen (1997), Concepts of Human Development and Poverty: A Multidimensional Perspective, Background Paper for Human Development Report, New York, undp.

5. Barrientos, A. (2004), "Latin America: a liberalinformal welfare regime?", in Gough, I. and Wood, G. D., Insecurity and welfare regimes in Asia, Africa and Latin America: social policy in development contexts, Cambridge University Press.

6. Bayón, M. C. (2009), "Persistence of an exclusionary model: Inequality and segmentation in Mexican society", International Labour Review, 148 (3), pp. 301-315.

7. Becerril, C. I. (2013), The role of the state in alleviating poverty: The mexican case and Oportunidades, PhD Thesis, University of York, Uk.

8. Behrman, J. & Hoddinott J. (2000), An Evaluation of the Impact of Progresa on Pre-School Child Height, Washington, D.C., International Food Policy Research Institute.

9. Bensusam, G. (2006), "Desempeño Legal y Desempeño Real: México", in Bensusam, G. Diseño Legal y Desempeño Real: Instituciones Laborales en Latinoamérica, México, Porrúa.

10. Bensusam, G. (coord.) (2007), Norms, Practices and Perceptions: Labour Enforcement in Mexico's Garment Industry.Executive summary, Mexico, Levi Strauss.

11. Bensusam, G. (2008), Regulaciones laborales, calidad de los empleos y modelos de inspección: México en el contexto latinoamericano, México, cepal.

12. Bensusam, G. and Middlebrook, K. J. (2012), Organised Labour and Politics in Mexico: Changes, Continuities and Contradictions. Institute for the study of the Americas, University of London.

13. Brunner J. J., Santiago P., García C., Gerlach J. and Velho, L. (2008), Reviews of tertiary education. Mexico. Organisation for economic co-operation and development (oecd).

14. Burnell, P. (2008), "Governance and conditionality in a Globalizing World", in Burnell, P. and Randall, V. (ed.), Politics in the developing world, Oxford University Press.

15. Cabrero, E. and Zabaleta, D. (2011), "Gobierno y gestión pública en ciudades mexicanas: los desafíos institucionales en los municipios urbanos", in E. Cabrero (coord.), Ciudades mexicanas: desafíos en concierto, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica.

16. Canales R. and Nanda R. (2008), "Bank Structure and the terms of lending for small businesses", Harvard Business School, Working Paper 08-101.

17. Cárdenas, O. J. (2009), "Poverty Reduction Approaches in Mexico since 1950: Public Spending for Social Programs and Economic Competitiveness Programs", in Journal of Business Ethics, 88 (0), pp. 269-281.

18. Chang, H. (2010), Things they don't tell you about capitalism, London, Allen Lane.

19. Congreso de los estados unidos mexicanos (2003), Ley del servicio profesional de carrera en la administración pública federal.

20. Congreso de los estados unidos mexicanos (2012), Ley Federal del Trabajo.

21. De Andrade, P. E., dos Santos, A. L., Krein, J. D., Leone, E., Proni, M. W., Moretto, A., Maia, A. G. and Salas, C. (2010), "Moving towards Decent Work. Labour in the Lula government: reflections on recent Brazilian experience", in Global labour university working papers, Paper no. 9.

22. De la Garza, E. (2011), "Los proyectos de reforma laboral en México, a marzo de 2011" in xiv Informe de Violaciones a los Derechos Humanos Laborales 2010, México, cereal.

23. Dussauge, M. I. (2011), "The Challenges of Implementing Merit-Based Personnel Policies in Latin America: Mexico's Civil Service Reform Experience", Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 13 (1), pp. 51-73.

24. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (eclac) (2004), Social Panorama of Latin America, Santiago de Chile.

25. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (eclac) (2010), Social Panorama of Latin America, Santiago de Chile.