Dossier: Photography, Visual Culture and History: Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives

Analyzing Historical Photographs: Genres, Functions, and Methodologies

Análise de fotografias históricas: gêneros, funções e metodologias

Analizar fotografías históricas: géneros, funciones y metodologías

Analyzing Historical Photographs: Genres, Functions, and Methodologies

Estudos Ibero-Americanos, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 6-16, 2018

Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul

Abstract: This article employs the concepts of genre and function as a contribution toward developing methodologies for analyzing photographs from a historian's perspective. The genre of photojournalism is examined in terms of the different functions carried out by what are defined as press photography, photojournalism, photoessays, and documentalism. It indicates that the misunderstandings generated by practitioners of the genre are a product of thinking that the rules of one function apply to the entire genre. It is hypothesized that historical analysis may be facilitated by establishing photographic genres, and distinguishing between the different functions therein.

Keywords: historical phootographs, photojournalism, genres.

Resumo: O artigo opera com os conceitos de genero e função como contribuição no desenvolvimento de metodologias para analisar fotografias desde uma perspectiva histórica. Examina-se o gênero fotojornalismo considerando-se suas diferentes funções delimitadas por suas diversas dimensões, entre as quais: fotografia de imprensa, fotojornalismo propriamente, fotoensaios e documentarismo. Observa-se que os enganos gerados pelos praticantes desse gênero fotográfico são resultado da aplicação das regras de uma única função a todo o gênero. Assume-se a hipótese que a análise histórica pode facilitar o estabelecimento dos gêneros fotográficos e a distinção das diferentes funções dentro de um gênero.

Palavras-chave: fotografias históricas, fotojornalismo, gêneros.

Resumen: Este artículo utiliza los conceptos de género y función en un esfuerzo por desarrollar metodologías para analizar las fotografías desde la perspectiva de un historiador o historiadora. El género del fotoperiodismo es examinado en los términos de las diferentes funciones llevadas a cabo por las que están definidas como fotógrafía de prensa, fotoperiodismo, fotoensayismo y documentalismo. Indica que los malos entendidos generados entre los practicantes de este género son un producto del pensamiento de que las reglas de una función se aplican al género entero. Hipotetiza que el análisis histórico se podría facilitar al establecer géneros de fotografía y distinguir entre las diferentes funciones que tienen dentro del género.

Palabras clave: fotografías históricas, fotoperiodismo, géneros.

What are we as historians to do with the overwhelming masses of photographic documents we confront in attempting to bring modern media into our discipline? How are we to organize them so as to avoid comparing apples and oranges? For many years, I assumed that the history of photography was a sub-genre of History of Art. I now think that photographic art is a genre of History of Photography. The date when I ceased to think that art history was the defining discipline of photographic study is etched clearly in my mind. In 2003, I was a member of a doctoral committee for a thesis defense on the US image maker, Winfield Scott, who worked in Mexico during the years 1888-1924 (MALAGÓN GIRÓN, 2003; 2012). The student's studies had been undertaken in the department of Historia del Arte, because there was nowhere else one could get an advanced degree in the history of photography within the UNAM. The thesis was extraordinary: the photographer was formerly little more than a rumor among photohistorians, in large part because his sometime partner, C.B. Waite, had erased Scott's identifying numbers and replaced them with his own. The research carried out by Beatriz Malagón Girón was impeccable, having investigated in 30 Mexican and 14 US archives. Her hypothesis was clearly established and supported: that Scott was an important example of the presence of US photographers connected to U.S. commercial interests in Mexico, alongside figures such as William Henry Jackson and Waite.

Mexican universities have a tradition of giving theses an honorable mention if deserved. After Malagón had left the room, the jury decided first that she had passed, and then we deliberated on whether she was to be given honors. When questioned, I said that there was no doubt in my mind that Malagón deserved the highest ranking. On the heels of my vote, a colleague from Historia del Arte firmly disagreed, “De ninguna manera. (No way). The student did not prove the aesthetic value of the photographs.” I was stunned, and then I started laughing as I replied, “These photos have no aesthetic value. They were made, usually commissioned, to sell real estate and tourism, as well as attract US investment”.

All of a sudden, I finally got it. I realized in a flash that the history of photography could not be a sub-discipline of Art History, because the methodologies of that discipline were not applicable to the vast majority of photographs. Photography is a medium before it is an art form, and artistic photography is simply one of the manifold photographic genres. However, as Ariel Azoulay argues, “Until the 1990s, the reciprocal relations between art and photography were dominated by a single template whereby the paradigm of art, with its attendant rules, was seen as the dominant – indeed the host – paradigm” (AZOULAY, 2012, p. 86). When we contemplate the enormous variety of photographs –for example, in the relatively large Mexican repositories of images – it is obvious that only a small percentage were made by avowed artists. In 1965, Pierre Bourdieu estimated that, “More than two thirds of photographers are seasonal conformists who take photographs either at family festivities or social gatherings, or during the summer holidays” (BOURDIEU, 1990, p. 19). As digital technology has placed cameras in the hands of (almost) everyone, we can assume that the percentage of family and friends photography to be significantly higher today. Given this statistic we could generously estimate that art photography might arguably comprise some five percent.

What are we to do with the other ninety-five percent? What sorts of methodologies are we going to utilize for what we might describe as photographic genres: photojournalism, family photography, portraits, imperial and subaltern photography, revolutionary and post-revolutionary photography, Indianist and indigenous photography, photography of and by workers as well as photography produced by companies, politically-committed photography, scientific photography, social scientific photography done by visual anthropologists and sociologists, photography made by the security forces, advertising photography, fashion photography, landscape and cityscape photography, organizational photography, architectural and industrial photography, photography of nature, postcards? The list will be very long – as it would be if we listed all the genres of writing – and, I believe that as we define the different photographic genres, each will require a particular methodology with which to analyze it.

I am here utilizing the concept of genre as a heuristic device, in order to begin to differentiate between types of photography and, hence, perhaps help in the development of methodologies to examine them within that context. The expectation brought to the source is fundamental in analyzing the information and meanings that are conveyed by the photographers and perceived by the viewers. As literary scholar E.D. Hirsch has argued, “[The reader] entertains the notion that ‘this is a certain type of meaning,’ and his notion of the meaning as a whole grounds and helps determine his understanding of details. This fact reveals itself whenever a misunderstanding is suddenly recognized. After all, how could it have been recognized unless the interpreter's expectations had been thwarted?…. Oh! You've been talking about a book all the time. I thought it was about a restaurant” (HIRSCH, 1967, p. 71-72).

Photographic genres are established by a number of factors: who they were made by, the context in which they were made, the objects pictured, the aesthetic conventions employed, and the uses for which they were intended as well as those to which they are put. Obviously, there are a number of greatly varying elements that function to differentiate photographic genres, but this problem can be seen in work on literary genres, which has a much longer history. As Tzetvan Todorov remarked, “The song is contrasted with the poem by phonetic traits; the sonnet differs from the ballad in its phonology; tragedy is opposed to comedy by thematic elements; the suspense narrative differs from the classic detective novel by the fitting together of its plot; finally, the autobiography is distinguished from the novel in that the author claims to recount facts rather than construct fictions” (TODOROV, 1976, p. 162). Of course, it is crucial to understand that the assignation of genre is only useful if we recognize its subjectivity: “If we believe that [classifications] are constitutive rather than arbitrary and heuristic, then we have made a serious mistake and have also set up a barrier to valid interpretation” (HIRSCH, 1967, p. 111)1. There will always be an over-lapping of the genres, and photographs can belong to different groups, depending upon the analysis being carried out.

I have encountered few texts dedicated to recognizing and distinguishing between the various functions photographs and photographers carry out, or that attempt to distinguish among the genres.2However, the necessity of doing so became apparent as I began to study photojournalism. My participation in the polemics produced by the misunderstandings between photojournalists that were generated by the Sexta Bienal de Fotoperiodismo in 2004 were crucial, but the first inkling I had about the different functions of photojournalists came as a result of an invitation by Eleazar López Zamora, Founding Director of INAH's Fototeca Nacional. Around 1988, Eleazar asked me to write a book about one of the archives in the Fototeca. He proposed three different possibilities. One was to continue in the line of workers’ history that I had been researching since I served as Coodinador de Historia Gráfica in CEHSMO (Centro de Estudios Históricos del Movimiento Obrero Mexicano) during 1982-83, and which had also been my focus in CIHMO (Centro de Investigaciones Históricas del Movimiento Obrero) in the BUAP. Eleazar thought I might find some topic related to analyzing the representation of workers in the Casasola Archive. Doing a sort of ethnohistory of the women workers in Mexico City nixtamal (corn meal) millsin December of 1919 had left me fascinated by the idea of using photographs to develop vignettes of working class life (MRAZ, 1982).3 However, that had been possible because of the extensive texts – letters from workers and reports from inspectors for the Secretaría de Industria, Comercio y Trabajo – that accompanied the photos in the Ramo de Trabajo of the Archivo General de la Nación. Such a tightly packaged bundle of graphic and textual information did not exist in relation to the Casasola Archive. I could have approached the study of the Casasola Archive from the standpoint of a historian, using photographs in terms of the ways their “transparency” offered the opportunity to do visual social photohistory, but the obstacles seemed great.4

The other two projects Eleazar had in mind would lead me in a very different direction. Studying either Tina Modotti or Nacho López would mean that my focus would fall more on the “representers” – the visions and intentions of Modotti and López – rather than the “represented”. Invited by Reinhard Schultz, Ihad participated in the first exhibit dedicated solely to her work, Tina Modotti: Photographien & Dokument, which opened in Berlin in 1989, and continues to travel around Europe (SCHULTZ, nd). I wrote an essay for the catalogue of that exhibit, and then published it in Mexico (MRAZ, 1989). However, despite the fact that the INAH archive has the world's largest collection of Modotti negatives, I decided not to continue to work on her, knowing that a number of studies were going to appear on her life and photography over the next few years.

Further, I felt that a work coming out of the Fototeca Nacional should advance the study of Mexican photography through a rigorous analysis of a photographer well-known within the country, but relatively unheard-of outside it, introducing him or her to a broader public. I chose to work on López in large part because of the insistence of Eleazar, for whose knowledge and judgment I had great respect. My interest in photojournalism had already been stimulated by the Hermanos Mayo, with whose archive I became familiar while at CEHSMO, prior to its purchase by the Archivo General de la Nación. I mounted an exhibit on them in 1984, Trabajo y trabajadores en México, 1940-1960, vistos por los Hermanos Mayo, the same year I carried out extensive interviews with Julio and Faustino Mayo; in 1988 I published what would be the first of my studies on them (MRAZ, 1988). I thought of López as more of an artist than a photojournalist, and told Eleazar that I would prefer to work on the Hermanos Mayo.

Over many meals and sobremesas, Eleazar both made it clear that the invitation was to work on a Fototeca archive, and convinced me to undertake the study of Nacho López. Once I had decided to work on López's photojournalism, Eleazar paid me a year's salary in exchange for giving courses to the rapidly expanding workforce in the Fototeca Nacional, which had received funding to carry out the digitalization and identification of the holdings. I gave one course on “The History of Mexican Photojournalism” and then another on “Nacho López;” as any professor knows, I learned an enormous amount by giving the classes, and I developed the basic structure for my book on Nacho. The great respect that continues to be given López's work in Mexico demonstrates Eleazar's prescience in this case and many others. In 2016, López was honored with an enormous exposition in Bellas Artes, the most important exhibit space in Mexico, and two large edited academic studies of his photography have recently been published (RODRÍGUÉZ and TOVALÍN AHUMADA, 2012; 2016).

From the very beginning, I limited my focus to his work as a photojournalist, for a variety of reasons. I find press photography vastly more interesting than art photography. Photojournalists have to work within a context that constrains their opportunities to express themselves: the politico-economic stance of their employer, the number of events they have to cover, and limited material they are given to work. Their possibilities to develop their own subjects and themes are also inhibited by the fact that their negatives (prior to the age of digitalization) almost always remained in the storerooms of the media that contracted their work; there, uncatalogued, they serve no purpose and are eventually destroyed. Hence, photojournalism embodies that Sartre an dialectic of doing something with what is being done to you. Being caught between your own aesthetic and social interests (for which reason an image maker chooses to work in photography) and the demands of the employing media places one in a Batesoni an “double bind.” The famous anthropologist, Gregory Bateson, remarked about the response to such a seemingly unresolvable situation: “If this pathology can be warded off or resisted, the total experience may promote creativity” (BATESON, 1972, p. 278, italics in the original).

Rodrigo Moya met this potentially schizophrenic situation head-on with his concept of the “double camera:” “Almost from the very beginning, I accepted that I had two cameras in my mind: one to comply with the news required by my employer, and the other to capture what I began to understand with a clarity and profundity that we learn from reality and a rebel's consciousness” (MOYA, s.d., p. 4). Photojournalism has a fundamental relationship to what we loosely call documentary photography. I believe that what is really new about photography is its indexical capacity, hence all photographs are documentary (with a tiny number of exceptions irrelevant to historians). News photography is one of the highest expressions of such indexicality, the realization of the really new.

I envisioned the book to be constructed in a series of concentric circles through which to eventually focus down on López's work. Hence, it was essential to know the history of Mexico in the 1940s and 1950s, a little-studied period. Within that wider circle, it was vital to construct a history of the Mexican press in those decades. Then, I needed to develop an in-depth knowledge of the illustrated magazines, and the work of their photojournalists so as to be able to compare them to López. I would also be contrasting López's expressive capacity and socio-political commitment to photojournalists whose work I was coming to know, among them the Hermanos Mayo, Héctor García, and Enrique Bordes Mangel. Finally, I would reach the nub of the topic: Nacho López's photojournalism, as well as his writings about it (largely produced in the 1970s). He published in the illustrated press for a relatively short period of time, 1950-60, limiting the number of magazines I would need to consult. Nonetheless, there were no studies on the Mexican illustrated magazines, and few on the press. I was to work my way, page by page, through 25 years of Hoy, Mañana and Siempre! Relying on the magazines’ tables of content was of little use, because I was also interested in discovering how his photography had been used outside of his photo essays, often without being credited to him. Further, I needed the experience of close contact with the magazines, and the opportunity to make my own indexes of their contents.

The literature on photojournalists and illustrated magazines in the US and Europe was just beginning to open up comparative possibilities, as well as issues and questions (VILCHES, 1987; FULTON, 1988; CURTIS, 1989; WILLUMSON, 1992; KOZOL, 1994). At the same time, I was becoming acquainted with the work of Alan Sekula, Sally Stein, Abigail Solomon-Godeau, and Martha Rosler, theorists who were exploring ways to analyze documentary photography and photojournalism (SEKULA, 1978; STEIN, 1983; SOLOMON-GODEAU, 1987; ROSLER, 1989). Prior to reading these studies, I had cut my teeth on works that were essential in redefining photography's space in academic analysis, and which continue to be fundamental in its study, such as those by Walter Benjamin, Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes, and John Berger (BENJAMIN, 1972; SONTAG, 1973; BARTHES, 1981; BERGER, 2013).

At that moment in Mexico, the reigning model of photo books on individual authors was to select a bunch of images around certain themes, assure good reproduction, and write (or have a well-known intellectual write) an introduction. I was determined to carry out an historical project instead, focusing López's work as a photojournalist. Through this strategy, I developed the method of creating an interface between López's intentions and those of the magazines, comparing the photographs he made (and saved) with those published.5 I also analyzed the ways in which they were cropped, in what sizes and on which pages they appear, as well as the texts that accompany them. López was largely considered to be among the elite of Mexican imagemakers, but my training as a historian required me to determine in just which ways López was an exceptional photojournalist, and that could only be accomplished by first constructing a backdrop of “ordinary” photojournalism. López only published in illustrated magazines, so I restricted my research to the publications Hoy, Mañana y Siempre! I had identified these periodicals as the most important of that medium in the period 1936-1960, an era that marked the rise and demise of the illustrated magazines as a center of mass media, as well as those in which López participated the most.

Almost immediately upon entering the project, I became disillusioned, and disoriented. This is not an uncommon experience among photohistorians because in many cases the images have had a prior popular circulation in coffee-table books – for example, the oft-reprinted images from the Casasola Archive– that have created an aura of “author” for individuals who were entrepreneurs as well as photographers. For many scholars in the past – before recent studies on the Casasolas – the discovery that the Casasola pictures had been taken by some 500 photographers left them baffled as to how to approach them. 6In the case of López, I had assumed that he was a “fotorreportero” dedicated to covering newsworthy events, as was made explicit in one of the few books then available on his work, Nacho López.Fotoreportero de los añoscincuenta (1989). Eleazar had told me that he was a critical leftist (part of his pitch to sell me on Nacho), so I expected to find marvelous images of social struggles and street battles. I had seen in the catalogue that the archive contained some 250 photos of the 1958-59 strikes, so went to Pachuca with much anticipation. I was sorely disappointed to discover that the photos López had chosen to conserve did not measure up to what I had seen by the Hermanos Mayo, Héctor García, and Enrique Bordes Mangel. Another rude awakening was learning that Nacho had not made a single image of the 1968 student movement; as he wrote in a letter, he “suffered a severe blow to my conscience” (“sufrí un golpesevero en la conciencia”) for not having participated in that struggle (LÓPEZ, 1980). So, what was López if not the press photographer I expected him to be?

The first problem is determining precisely what we understand as photojournalism. To define it in the easiest way, we could say that it is constituted by images made for periodical publications. Nevertheless, though it appears to be a relatively easy genre to define, in fact it poses real difficulties. At one extreme we find a photographer working in a daily newspaper such as Ovaciones, for example, who must cover five orders a day, for which he was given a roll of 25 exposures (predigital), and directed to take, in the oft-repeated phrase of Mexican photojournalists, “Five photos in each order; not one more, not one less.” At another extreme of photojournalism we find Sebastião Salgado, who can dedicate himself to projects for six or more years (though he publishes selections of his photos in media such as The New York Times during that period); in one documented instance, he shot nearly 600 images a day (SAUNDERS, 1999, p. 112).

The field of photojournalism is wide and varied, but one basic consideration is the publication for which the images are made. A press photographer who takes pictures for the daily press is tied to the necessity of providing information encapsulated in one image. Photojournalists who publish in magazines are further from immediate events; their photos many times form part of reportages with greater profundity and multiple images, because of the need to construct a narrative. A member of the Hermanos Mayo, the most prolific photojournalist collective in the history of Latin America, Cándido Mayo described the difference between working in a daily and for a magazine, “A reporter can and ought to be an artist at the same time, if he is working in a magazine. However, if he is photographing for daily newspapers, sometimes the urgency, the rapid events, oblige him to leave aside his preoccupation for the light, the shadows, and the angles” (ANTONIORROBLES, 1952, p. 42).

In general terms, I believe there are two key considerations that help us understand the differences between the diverse types of photography produced in the mass media. The first is the question of authorial control, which is manifested in different ways during the three stages of production: the “conception,” the “realization,” and the “edition.” In other words: To what degree is the photographer the source of the original conception for the article? What control does he or she have over the photographic act? What power does he or she have in relation to the edition of the article? And, the all-important question: What control does the photographer retain over their negatives; that is to say, to what extent can a photojournalist be said to be carrying out a project of interest to them, as well as covering the events they have been assigned (as with Moya's “double camera”)?

Related to the question of authorial control is the degree of direction assumed by the imagemaker during the photographic act. An example of minimal direction would be that of a situation in which a photographer simply “covered” an occurrence over which he or she would appear to have had no influence. At the other pole are photoessays for which a photographer has created “events,” either by constructing the scene or by composing the essay from their archive. Between these two extremes we find inexhaustible variations of directed photography: for example, images that, however spontaneous, nevertheless demonstrate the effect of the photographer's presence, as well as those in which people pose and openly collaborate, and, to a greater or lesser degree, fashion their own image (MRAZ, 2002, p. 2004).

We could formulate a heuristic hierarchy in order to delineate the differences between the various groups, bearing in mind that I am here describing functions and not persons, because photojournalists change their roles according to the concrete situations in which they find themselves. Such an order would describe the gamut from those with less control to those with more autonomy, in the following order: press photographer, photojournalist, photoessayist, documentalist (rather than documentarian). To exemplify: the Hermanos Mayo functioned as press photographers when they worked for daily newspapers, as photojournalists when they composed their magazine articles, and as documentalists when they took pictures in the street while going to or coming from assignments. The Mayo do not appear to have constructed photoessays, which is the bailiwick of Nacho López, who also was a documentalist. This hierarchy does not assign values to the different roles, but instead uses these categories as a way of indicating the great variety of ways in which photographers function within newspapers and magazines, and which of these activities we must take into consideration in analyzing them.

According to this schema, press photographerswork in daily newspapers, and have little input in the conception of a story, because it is most probable that they have been assigned to cover events, as in the Hermanos Mayo photo of the battle between teachers and police in the Zócalo during the 1958 strikes (Photo 1).

Photo 1

Hermanos Mayo. Striking teachers battle with police, Zócalo, Mexico City, 6 September, 1958. Fondo Mayo, Chronological Section no. 12754, Archivo General de la Nación.

Their degree of authorship is determined by the occurrence itself, by the amount of film they have been given (or bring themselves, as with the Mayos), by the pressure of time imposed by other assignments they have that same day, and by the limitations set for publication that have been established in their workplace, and which they have more or less internalized as self-censorship. They have no say in the edition of their imagery. In Mexico (and elsewhere), the great majority of photographers in periodical publications have functioned as press photographers.

In a book produced by the Associated Press, “The News Photographer's Bible,” AP photojournalist Ed Reinke provided a classical formulation of how press photographers are expected to work: “As for photojournalism, and I emphasize the word journalism, we make photographs from the circumstances we are given and we don't try to alter those circumstances” (HORTON,1990, p. 51). Those who earn their living covering “hard news” on a daily basis have very specific opinions about what constitutes the ethics of their guild, as came to float in the polemics that took place around the awards of the Sexto Bienal del Fotoperiodismo of 2004 in Mexico City. There, in the “Polémica y debate abierto, ”Mexican photojournalists made explicit their ethical position, which I would summarize in the following ways. They argue that the commitment of photojournalists is to capture reality, of which they are simple witnesses, in order to inform with honesty, transparency, and veracity. Because the images they record are irrefutable and lasting, the first version of history, the only thing they should create are documents. Hence, staging scenes is not allowed, nor can one pose or recreate them nor can the original shot be “manipulated” in a darkroom or by Photoshop, because to do so would be to lie and trick. They see themselves as dedicated to spontaneously discover the unknown that occurs in a fraction of a second, so it is not acceptable to copy or be inspired by prior photographs (“Polémica y debate abierto”, 2004; DE LA PEÑA, 2008). I would describe the position of the press photographers in this controversy to demonstrate a misunderstanding: they confused the rules of a particular function, that of “hard news,” with those of the entire genre of photojournalism.

In my schema, photojournalists are distinguished from press photographers by the fact that they usually work for magazines. This allows them to dedicate more time to a story, to take and publish more images, and to construct a narrative. Phillip Jones Griffiths, a member of Magnum, believes that these categories began to take shape during the 1930s because,

The terminology in photography is almost entirely based on fragile egos. If you were a Fleet Street photographer [British press reporter] in the 1930s, the last thing you ever wanted to do was be confused with someone who did weddings or bar mitzvahs…. And in turn, the guy that starts working for Picture Post magazine who goes to Africa for three months to do a story on the wind change in Africa is pretty anxious not to be confused with a press photographer, especially because press photographers for the most part [were considered to] have a very limited vocabulary and big ears and wore strange hats with “Press” stuck in the band. So, he was anxious to call himself something different, so he called himself a photojournalist (FULTON, 1988, p. 188).

Photojournalists would have more control than press photographers over the conceptualization of a project, and may be the originators of the ideas for stories. In the realization stage, they would also have more autonomy, given the fact that their film would be less limited, and the question about what they could or could not publish may have been discussed in an explicit way, in which they may have had some input. The question of whether or not they can (and are allowed to) write the texts is fundamental: López was perhaps the only Mexican photojournalist that wrote the texts to (some of) his essays, as he did for “Solo los humildes van al infierno” (Only the poor go to hell), when he spent four weeks photographing in the holding cells of Mexico City's police stations (Photo 2).

Photo 2

Nacho López. Young woman in police station, Mexico City, 1954. Fondo Nacho López, INAH, Fototeca Nacional, 405677.

Usually, however, they would probably have little to say about the editing of the story, but their possibilities of intervening would still be greater than would be those of the press photographers. Moreover, their general function is to relate “human interest features,” which allows for a certain tolerance of staging that would not be permitted in hard news; for example, Eugene Smith was fond of directing his reportages (WILLUMSON, 1992). Almost all directed photojournalist images were made within the category of features, although their credibility is, to a great extent, a result of seepage from the faith generated by hard news imagery.

Distinguishing between a reportage and an essay is fundamental in differentiating what I am calling a photojournalist from a photoessayist. Reportage involves covering a news event or, at the very least, a “live” activity. Thus, in general terms, we could say that reportage has its source in the world, in “reality.” An essay, on the contrary, tends to originate in the photographer's mind, and in the interest of exploring an idea that existed prior to realizing the photographic act. An essay can be about something “live,” but it is distinguished from reportage by the extent to which the photographer's conceptualization has preeminence over the communication of information about an event. Hence, photoessayists would have the greater degree of authorial control within periodical publications.

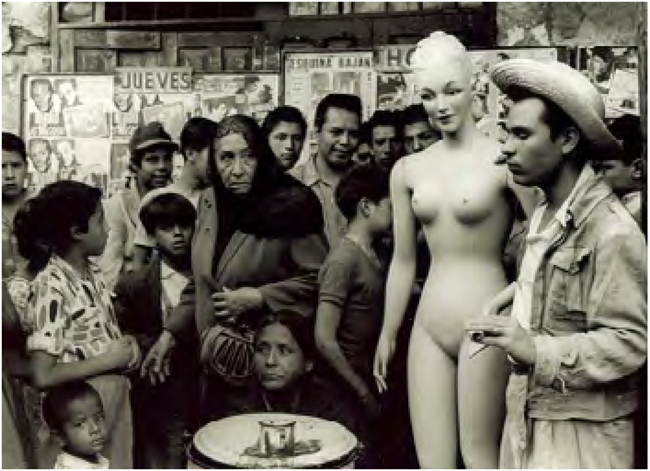

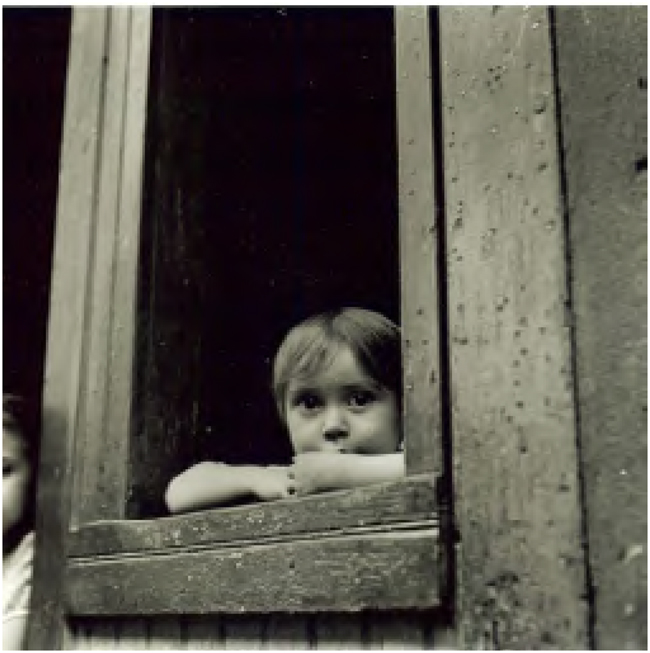

The photoessay sometimes originates with photo-journalists such as López, above all if they can write the texts as well. Because they are looking for ways to express their conceptions, they often attain a greater directorial control over the photographic act, which may include staging scenes that provoke reactions from spectators in the frame, for example, the woman who staresat the mannequin that a man hired by López is carrying around in the street (Photo 3). They also compose photoessays from their archives, in which the date and place of the photograph is elided. For example, López's image of a little boy looking out his window was taken in Venezuela during 1948 (Photo 4). However, he included it in the photoessay, “Yo también he sido niño bueno” (I've been a good kid too), which ostensibly presented the disappointment of poor Mexican children who will not receive Christmas gifts because of their families’ poverty. Although the photoessay was published in the magazine Mañana on 30 December 1950, it was described as a “reportaje,” giving the impression that López had encountered these scenes in Mexico during the Christmas season of that year (LÓPEZ, 1950, p. 20). As Nacho said of working in the illustrated magazine, “… Mañana, where I was given absolute liberty in the choice of themes and the format of my articles. My old friend Esteban Cajiga even [allowed me] to stick my nose into supervising the negatives and the offset impressions” (LÓPEZ, 1984, p. 11). López was much respected by the great editor of Mexican illustrated magazines, José Pagés Llergo, for his extraordinary technical and narrative skills.

Photo 3

Nacho López. Man with mannequin in a group, Mexico City, 1953. Fondo Nacho López, INAH, Fototeca Nacional, 405642.

Photo 4

Nacho López. Child peering out window, Venezuela, 1948. Fondo Nacho López, INAH, Fototeca Nacional, 405763.

What I describe as documentalists are those which enjoy the greatest liberty of expression. We often loosely define documentary photography, usually by opposing it to art photography. Here, it is important to note that, though all photojournalism is documentary, I am here using the concept of documentalist to describe particular situations, within which a variety of possibilities exist to pursue one's own interests. Mexican photographers who work for institutions are sometimes allowed to test the limits; one example is the Instituto Nacional Indigenista (INI, National Indigenist Institute), where Nacho López was contracted during and after leaving photojournalism. In the United States the best instance would be the Farm Security Administration, and its photographers such as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Jack Delano, and Arthur Rothstein. Evans openly testified to the latitude he experienced, “I was interested, selfishly, in the opportunity it gave me to go around and use the camera. I did anything I pleased, and ignored what I was expected to do (STOTT, 1986, p. 319). Another possibility is to be a “free lance” photographer who lives from grants, book royalties, and commissions from state governments or banks, often in conjunction to being a member of an agency.

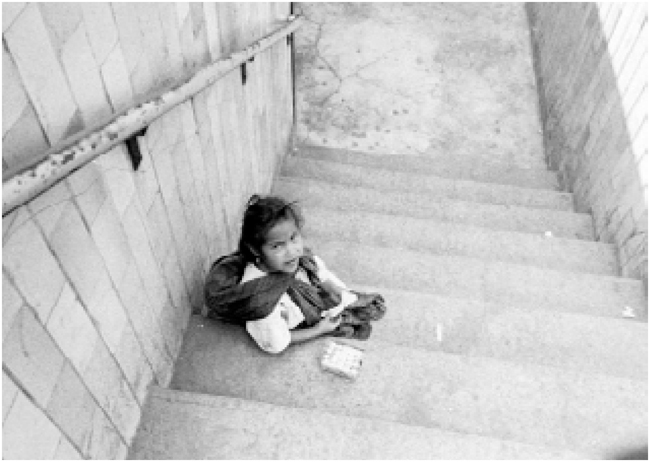

Finally, we would have to consider those images that photojournalists make on their own initiative, whether while they are working or in their free time; this factor bears an intimate relationship to whether the photojournalists conserve and catalogue their negatives. Salgado has often said that his work is closer to documentary photography than to photojournalism, whereas Nacho López always insisted that he was a photojournalist. The Mayo were much more photojournalists than documentalists, but one of the best examples of their work in this function is the picture Mayo made of a little girl selling chewing gum outside one of the Mexico City subway stations (Photo 5).

Photo 5

Hermanos Mayo. Young girl selling chewing gum at subway entrance, Mexico City, c. 1960. Fondo Mayo, Imágenes de la Ciudad, Archivo General de la Nación

We know that this image is unrelated to a work order because it is found in the largest section of the immense Mayo archive where a half a million negatives are stored under the category of “Imágenes de la ciudad” (Images of the city). Hence, we can assume that Mayo took the picture while on the subway going to or coming from a work order. It is a magnificent representation of how Mexican children are ensnared in lives of poverty: the high-angle shot entraps and encloses the girl in the concrete walls – a powerful metaphor for the metropolitan jungle of Mexico City – just as the education she is missing while selling gum will assure that she will never be able to leave her marginal existence.

In summation, the various research projects I have carried out on Latin American photojournalism have led me to understand the differing functions within that genre (MRAZ, 1994; 1998; 2002; 2003; 2009; 2012; MRAZ and VÉLEZ STOREY, 1996; MRAZ, et al., 2009). I believe that the method of focusing on the varying functions within genres can be applied fruitfully to other types of photography. For my upcoming book, I now plan to implement this strategy to studying genres such as imperial, neocolonial and decolonial photography; Indianist photography; worker photography; and revolutionary photography. The task is complex, but the objective is to participate in finding ways in which historians can begin to sort out this enormous body of historical documents so as to teach us how to incorporate photographs rigorously in our discipline. I hope to discover the right questions, as much as offer answers. As the Cuban poet, José Lezama Lima wrote in 1971: “La grandeza del hombre es el flechazo, no elblanco” (Human greatness is the arrow's flight, not the bull'seye) (COSTA LIMA, 1992, p. 152).

References

ANTONIORROBLES. En la ruta de Paco Mayo. Ma-ana, Mexico City, n. 449, p. 40-44, Apr. 1952.

AZOULAY, Ariella. Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography. Trans. Louise Bethlehem. London: Verso, 2012.

BARTHES, Roland. Camera Lucida. Trans. Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981.

BATESON, Gregory. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine Books, 1972.

BENJAMIN, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In: LANG, Berel; WILLIAMS, Forrest (Ed.).

BERGER, John. Understanding a Photograph. Edited by Geoff Dyer. London: Penguin Books, 2013.

BOURDIEU, Pierre. Photography: A Middle-brow Art. Trans. Shaun Whiteside. Cambridge: Polity Press 1990.

Costa LIMA, Luiz. The Dark Side of Reason: Fictionality and Power. Trans. Paulo HenriquesBritto. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1992.

CURTIS, James. Mind's Eye, Mind's Truth: FSA Photography Reconsidered. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989.

DE LA PEÑA, Ireri (Ed.). Ética, Poética y Prosaica. Ensayos sobre fotografía documental. Mexico City: Siglo XXI, 2008.

DERRIDA, Jacques. The Law of Genre. Glyph: Johns Hopkins Textual Studies, Baltimore, n. 7, p. 202-232, 1980.

Escorza RODRÍGUEZ, Daniel. Agustín Víctor Casasola. El fotógrafo y su agencia. Mexico City: INAH, 2014.

FULTON, Marianne. Eyes of Time: Photojournalism in America. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1988.

GALEANO, Eduardo. Memoria del fuego. Three volumes. Mexico City: Siglo XIX, 1982-1986.

HIRSCH Jr., E. D. Validity in Interpretation. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1967.

HORTON, Brian. The Associated Press. Photojournalism Stylebook. The News Photographer's Bible. New York: Addison- Wesley, 1990.

KOZOL, Wendy. Life's America: Family and Nation in Postwar Photojournalism. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994.

LÓPEZ, Nacho. Letter to Manuel Berman, 1 August 1980, Archivo Documental Familia López Binnqüist (ADFLB).

______. Yo, el ciudadano. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1984.

______. 'Yo también he sido ni-o bueno…', un reportaje de Nacho López. Ma-ana, Mexico City, n. 383, p. 20-26, Dec. 1950.

______. Winfield Scott: Retrato de un fotógrafo norteamericano en el porfiriato. Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, 2012.

Marzal FELICI, Javier. Cómo se lee una fotografía. Interpretaciones de la mirada. Madrid: Cátedra, 2015.

MOYA, Rodrigo. Unpublished manuscript. Las imágenes prohibidas. ENCROME 4, “Proyecto ENsayo-CRÓnica-MEmoria”, Archive of Rodrigo Moya.

MRAZ, John. “En calidad de esclavas”: obreras en los molinos de nixtamal, México, diciembre, 1919. Historia Obrera, Mexico City, v. 6, n. 24, p. 2-14, Mar. 1982.

______. Los Hermanos Mayo: el Primero de Mayo y la fotografía de la clase obrera. Boletín de investigación del movimiento obrero, Puebla, n. 11, p. 105-115, Mar. 1988.

Tina Modotti: en el camino hacia la realidad. La Jornada Semanal, Mexico City, n. 7, p. 20-23, July 1989.

Cuban Photography: Context and Meaning. History of Photography, London, v. 18, n. 1, p. 87-96, Spring 1994.

Mexico: The New Photojournalism. History of Photography, London, v. 22, n. 4, p. 313-365, Winter 1998.

Sebastião Salgado: Ways of Seeing Latin America. Third Text, v. 16, n. 1, March 2002, 15-30.

What's Documentary about Photography? From Directed to Digital Photojournalism. In: Zonezero Magazine, 2002.

Nacho López: Mexican Photographer. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

From Robert Capa's “Dying Republican Soldier” to Political Scandal in Contemporary Mexico: Reflections on Digitalization and Credibility. In: Zonezero Magazine, 2004.

Looking for Mexico: Modern Visual Culture and National Identity. Durham: Duke University Press, 2009.

Photographing the Mexican Revolution: Commitments, Icons, Testimonies. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012.

MRAZ, John; VÉLEZ STOREY, Jaime. Uprooted: Braceros in the Hermanos Mayo Lens. Houston: Arte Público Press, 1996.

MRAZ, John et al. Walter Reuter. El viento limpia el alma. Barcelona, Lunwerg, 2009.

Nacho López, fotorreportero de los a-os cincuenta. Mexico City: CONACULTA, 1989.

PICAUDÉ, Valérie; ARBAÏZAR, Phillippe (Eds.). La confusión de los géneros en fotografía. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 2004.

“Polémica y debate abierto,” Sexta Bienal del Fotoperiodismo, Mexico City, 2004.

RODRÍGUEZ, José Antonio; TOVALÍN AHUMADA, Alberto (Eds). Nacho López, ideas y visualidad. Mexico City-Veracruz: INAH-Fondo de Cultura Económica-Universidad Veracruzana, 2012.

Nacho López. Fotógrafo de México. Mexico City: Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes, 2016.

ROSLER, Martha. In, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography). In: BOLTON, Richard (Ed.). The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography. Cambridge, MIT Press, 1989. p. 303-341.

SAUNDERS, Dave. 20th Century Advertising. London: Carlton, 1999.

SCHULTZ, Reinhard (Ed.). Tina Modotti: Photographien Dokumente. Berlin: Sozialarchiv, nd [1989].

SEKULA, Alan. Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary. The Massachusetts Review, Amherst, v. 19, n. 4, p. 859-883, 1978.

SOLOMON-GODEAU, Abigail. Who is Speaking Thus? Some Questions About Documentary Photography. In: FALK, Lorne and FISCHER, Barbara Fischer (Eds.). The Event Horizon. Toronto, Coach House Press, 1987. p. 193-214.

SONTAG, Susan. On Photography. New York: 1973.

STEIN, Sally. Making Connections with the Camera: Photography and Social Mobility in the Career of Jacob Riis. Afterimage, Rochester, v. 10, n. 10, p. 9-16, May 1983.

STOTT, William. Documentary Expression and Thirties America. London: Oxford University Press, 1986.

TODOROV, Tzvetan. The Origen of Genres. New Literary History, Baltimore, n. 8, v. 1, p. 159-170, 1976.

The Typology of Detective Fiction. In: The Poetics of Prose. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977. p. 42-52.

VILCHES, Lorenzo. Teoría de la imagen periodística. Barcelona: Ediciones Paidós, 1987.

WILLUMSON, Glenn W. W. Eugene Smith and the Photographic Essay. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Notes