Artículos

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional.

Recepción: 10 Septiembre 2018

Aprobación: 15 Octubre 2018

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3344844

Abstract: In Ecuador, some political operators achieved a legal disposition that allows high amounts of illicit substance consumption without addressing the other parts of the production and distribution chain. Although the defenders of the consumption table use sources of critical criminology, it is observed that such an approach is not relevant without addressing the context, that is: the criminal situation and the apparatuses of social control in operation. This article points out the danger of: a) allowing an undesirable increase of the criminal opportunity, b) erroneously assuming that the consumption table will lead to abolition,c) confusing the existence of a process of criminalization ofthe subordinate sectors with converting the delinquent in a political actor of democratic change. At the same time, several researchers indicated how the relationship between the decree of the tenure or consumption table and the increase in criminal activities took place.

Keywords: consumption tables of illicit substances, criminal situation, critical criminology, abolitionism, Ecuador.

Resumen: En Ecuador, algunos operadores políticos lograron el decreto de una disposición que permite altas cantidades de consumo de sustancias ilícitas sin atender las otras partes de la cadena. Si bien los defensores de la tabla de consumo utilizan fuentes de la criminología crítica, se observa que tal enfoque no es pertinente sin abordar el contexto, esto es: la situación delictiva y los aparatos del control social en funcionamiento. Este artículo señala el peligro de: a) permitir un aumento no deseable de la oportunidad criminal, b) asumir erróneamente que la tabla de consumo llevará a la abolición, c) confundir la existencia de un proceso de criminalización de los sectores subordinados con convertir al delincuente en un actor político del cambio democrático. Al mismo tiempo, varios investigadores indicaron cómo se producía la relación entre el decreto de la tabla de tenencia o consumo y el aumento de las actividades delictivas.

Palabras clave: tablas de consumo de sustancias ilícitas, situación criminal, criminología crítica, abolicionismo, Ecuador.

1. INTRODUCTION

In Ecuador, the drug policy is constitutive to the action of the State. This is largely explained by the fact that most of the coca and cocaine in the world is produced in neighboring or nearby countries: Colombia, Peru and Bolivia. This puts this small Andean nation at the center of the global trafficking of illegal substances. Indeed, the UN (UNODC: 2015, p.33) recognizes that Ecuador is the 4th country in the world according to drug seizures, after Morocco, the Netherlands and Colombia. The UN has also measured an increase of at least 3 times the hectares of coca crops in Colombia between 2012 and 2016 (UNODC & Gobierno de Colombia: 2017, p.23), many of them in a thick stripe bordering the North of Ecuador (Castro Aniyar: 2015). As a result, acute seizure peaks occur in coastal and border areas of the country.

Additionally, the northern border, corresponding to the Colombian and narco-producers Departments of Nariño and Putumayo, consists of just 585 km of land with more than 41 pathways of an enormous permeability according to the Police (more than 60 steps according to the Ecuadorian Armed Forces) and relative under control, not counting the maritime frontiers. Through these pathways and the maritime channel there is, in addition to the drugs for export, an important income of illegal substances such as marijuana, creepy, base paste, “H” (local heroine) and low purity cocaine hydrochloride, basically all of residual origin, intended for domestic consumption (Castro Aniyar: 2015).

Main objective of domestic market of illicit substances are consumers in the most important urban locations. This market in Ecuador is called "micro-trafficking".

In this country, drug addiction is considered a public health problem, so the State is responsible for developing information, prevention and control programs on the consumption of narcotic and psychotropic substances, as well as offering treatment and rehabilitation to occasional, habitual and problematic consumers (Asamblea Constituyente: 2008). Therefore, the legislation urges the creation of the Intergovernmental Council on Narcotic and Psychotropic Substances (CONSEP, in Spanish) for 2013, in order to regulate matters related to this topic. The constitutional framework warns against criminalizing consumption and states the need to treat this problem from an "integral" approach.

This led to a debate within CONSEP about the nature of consumption, which resulted in the enactment of a tolerance or tenure table for consumers. Previous to this table, all tenure was considered illegal.

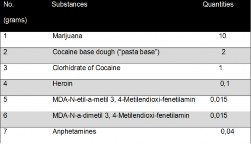

001-CONSEP-CO-2013 table is in force since July 2014, and reflects the position favorable to therelaxation of the consumption spectrum, through relatively high grammages. For example, it allows possession in a single person of 20 marijuana doses, 10 lines of cocaine, 20 doses of base paste and, in the case of heroin, another 20 doses. The table does not present limits of periodicity, nor of mixture of substances. Which would mean that, for example, a person could be authorized to consume, in a single day, 20 doses (marrow or bundles) of marijuana and 10 lines of cocaine, renewable the next day.

The arguments favorable to this relatively high consumption table are usually taken from authors and reflections of critical criminology and other subsidiaries. This article will analyze the theoretical problems and the evaluation of policies, based on the same critical premises, produced by implementing this consumption table without attending to relevant empirical studies.

2. THE ARGUMENTS FAVORABLE TO HIGH CONSUMPTION

Authors who favor the current table maintain the need to tolerate relatively high doses of tenure for main illicit drugs. The following are the basic arguments:

a) The consumer is presented as "a subject of rights within the framework of the exercise of the autonomy of his will or of personal free development"1 (Paladines: 2017, p.13).

b) The same idea that the consumer is a subject of rights is projected to the idea that there is a non- restricted right to consumption in Ecuador. This follows from the practical observations of the application of the law in the case of Daniel L: Having widely exceeded the tenure allowed by the same defended table, it is considered that the imprisonment of Daniel L. is a "distortion of the criminal system" and warns of the danger of “repeating":

“From an ethnographic perspective, the use of cannabis for recreational purposes is related to group practices. Hence, the quantities for their supply can exceed the permitted thresholds according to the policies of their States. [but] These are cases that are fully investigated by police agencies, generating practices that could criminalize simple consumers. Ecuador has not been the exception. The administration of justice has reported incidents of arrests and convictions of simple users, as occurred in the case of Daniel L. whose [marijuana] possession exceeded 80 grams (Corte Nacional de Justicia, 2014: sentencia 197 LBP). This distortion of the penal system can be repeated, since the "counter-wave" reduced the margins from 300 to 20 grams in cases of possession of cannabis for small-scale trafficking" (Paladines: 2017, p.23)

c) Restricting the table of tenure associated with consumption corresponds to criminalizing the consumer (Drafting Security: 2017; Paladines: 2017).

d) The micro-trafficking activity corresponds to very small businesses that poorly affect the large distributors, who constitute the real problem (Paladines: 2017; 2015).

e) Criminalizing micro-trafficking through the “criminalization of consumption” would lead to a costly increase in the prison population, mainly from vulnerable social strata, which the State could not control in the short term (Paladines: 2017). On the contrary, the tenure of high doses would make more difficult the criminalization of the consumer and poverty. So it would reduce the penitentiary population.

f) Decriminalizing a possession or broad possession of drugs would prevent the consumer from being confused with a drug trafficker:

"The thresholds established in Resolution 001-CONSEP-CO-2013 fill the gap that has the principle of not criminalizing consumption, whose reality never had a parameter to avoid users being confused by drug traffickers"(Paladines: 2013).

This would lead to confuse health policies with security (Redacción Seguridad: 2017).

g) The restriction in the consumption table would contradict the fact that the non-criminalization of drug consumption is a constitutional right that cannot be legally limited (Paladines: 2017; 2013).

h) A restricted grammage of consumption would lead to greater police activity on daily life, favoring the creation of a "Police State" (Barreto: 2015a; 2015b; Paladines: 2015).

i) The underlying problem would reside in a problem identified by abolitionism within critical theory (Christie: 1982), whereby any penalty from the criminal system would be arbitrarily generating pain, and therefore is ethically inconsistent:

"With this, the special positive prevention (rehabilitation / reintegration) lacks the duty to be, because it ontically places [,] as a being of deprivation of liberty [,] an instance to generate suffering or pain on people. The mere fact of being imprisoned means pain, or punitiveness. Therefore, imprisonment is a penalty, a pain that possibly has no limits against reason or the same legal system (...) In the middle of this debate, Ecuador tightened the nut of its criminal policy on drugs" (Paladines: 2017, p.5).

j) Contrary to what the securitist approaches promise internationally, increasing penalties or reducing consumption tables would not guarantee efficient results:

"(...) because after having adopted a security approach, the levels of consumption and their lethality [of the drug] have not diminished (...) The strongest criticism points to the centrality of the punitive as a strategy that, on the contrary, it has contributed to a further deterioration of States and societies. Thousands of deprived of their liberty by the ‘hard hand’ of the security agencies (Uprimny et al, 2012), and thousands of deaths by the ‘hard hand’ of the cartels is the outcome of a world political crisis that still resists deciphering and accepting the 'new approaches' on drugs" (Paladines: 2017, pp.6-7).

3. WEAKNESSES OF THE TABLE OF CONSUMPTION ACCORDING TO EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

Various sources investigated the impact of the consumption table on criminal activities, incarcerations and on the dynamics of control of territories by crime in small territories. This was possible thanks to the fact that the validity date of the consumption table allowed a before and after on a relatively constant set of variables of criminal policy and criminometric instruments.

The first investigation was produced by an inter-agential team, based on police statistics (Dirección Anti- Drogas et al.: 2015). The second was also carried out inter-agential team but this time, between the National Secretariat of Science and Technology and the Ministry of the Interior (Castro Aniyar: 2018; 2015).

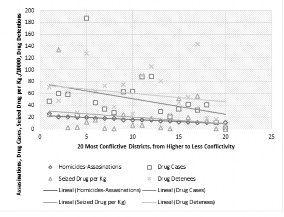

In the first place, it is demonstrated, based on the dynamics of the police and military action of that period, that the crimes registered in the 20 most violent territories of the country are almost directly proportional to the activity caused by the market of illegal substances. It happens clearly in the curves "drug cases", "seized drug", "drug detainees" and even "homicides", which we use to measure "violence": the greater the conflict, the greater the activity linked to illegal substances. These territories are not, for the most part, territories of large-scale trafficking, but are constitutive of the urban fabric of the large cities where micro-trafficking activities prevail over those of drug trafficking for export. The described categories are shown below:

Figure 1

Dispersion curves for (drug crimes + violence) x (20 most conflictive territories in the country ordinated for crimes in general). Own graph from Dirección Antidrogas et al., 2015.

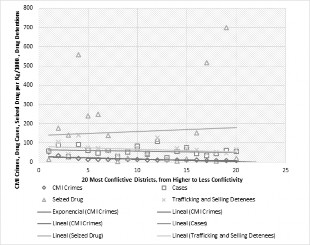

When the variable "homicides" is extracted and common crimes are included instead, basically, against property offenses and assaults, the curve related to seizures is “released”, showing that homicidal violence is more related to large-scale drug trafficking. However, the trend that associates daily cases of micro-trafficking drugs with common crimes continues (Dirección Anti-Drogas et al.: 2015).

Figure 2

Dispersion curves for (drug crimes + non-violent crimes -CMI-) x (20 most conflictive territories in the country ordinated for crimes in general). Own graph from Anti-drug Direction et al., 2015.

These two tables show that the greater the large drug and micro-trafficking activity, corresponds to a greater common crime behavior, in the territorial axis.

This is confirmed in another quantitative-qualitative research aimed at small territories (Castro Aniyar: 2018). There it was visible that the activities of the same drug traffic in small scale generate means of strategic appropriation of the territory that facilitate the commission of crimes and their expansion in the neighborhoods and cantons of Ecuador.

This research showed that, almost invariably, between 80 and 90% of the most threatening and recurring hotspots in the North of Quito, the Center of Quito, the South of Quito, the South of Guayaquil and the Province of Esmeraldas correspond to the same places where drugs are sold or consumed (fundamentally, both marijuana and cocaine basic dough –pasta base in Spanish-).

The applied instruments showed that high tenures favor micro-trafficking, since the simultaneous possession of one person a day of 20 bundles of marijuana, 8 lines of base dough, 4 lines of cocaine and 20 doses of local heroin, was an appropriate context for the development of camouflaged micro-trafficking and not consumption. In this investigation, ethnographic observations, police interviews and composed cognitive maps applied showed that simulated consumers can sell several times the same amount of 10 grams, for example, of marijuana, per day. Since each package of 10 grams of creepy marijuana can cost around 12 dollars in the neighborhood market and, since this amount, multiplied by working days, is close to an Ecuadorian minimum wage per month, the market looks attractive, this is, without considering other drugs, distribution networks, political gains, or other strategies to reduce costs (Castro Aniyar: 2015)2.

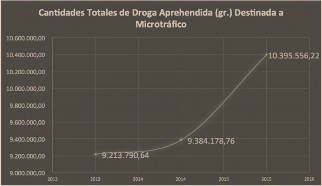

Triangulating the previous information with the timeline, the same one in which it is possible to observethe concrete effect of the consumption table, it is obtained that, all the micro-trafficking activity, including the apprehensions of people, increased clearly from July of the 2013.The following figure shows how seizures increased, only at the micro-trafficking level, as of the 2nd semester of 2014, the date on which it is possible to observe the effects of the resolution table 001-CONSEP- CO-2013.

Figure 3

Increase in Microtrafficking Seizures before-after the Table of Tenure from July 2014.

Dirección Anti-Drogas et al., 2015

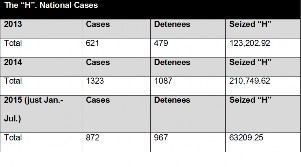

The following figure shows the before-after increase in arrests for micro-trafficking heroin (the "H").

Figure 4

Increase in the supply of Heroin for Internal Consumption by Cases and Detainees. 2013- July 2015. Ministerio del Interior, 2015.

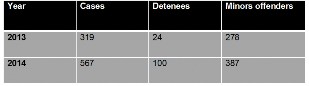

Worryingly, this increase in detainees particularly affects the elementary schools of Ecuador in the period studied:

Figure 5

Increase in Anti-Drug Activity in Schools. Dirección Anti-Drogas et al., 2015

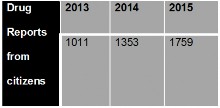

When triangulating this data with reports and tele-reports by drugs (1800 DROGAS, 1800 DELITO, DINAPEN, Public Prosecutor's Office, Ministry of Interior and Community Police), it is possible to estimate that criminal activity for illegal substances has increased as a whole during the studied period, and not just police activities:

Figure 6

Increase of Reports on Microtrafficking from citizens. Dirección Anti-Drogas et al., 2015

4. CRITICAL CRIMINOLOGY APPROACHES

In advance we apologize for the brevity of the following strokes for the purposes of this article: Very roughly, we call critical criminology a set of authorial theories and matrices that began with the approaches initiated by the Labeling Approach and the New Criminology in the 60 and 70 of the twentieth century, which evolved into other streams such as abolitionism, left realism, critical criminology proper and minimal criminallaw. Although the concept was coined in the 70s in Latin America by criminologists of social control (Aniyar de Castro & Codino: 2013; Anitua: 2010, Baratta: 1999; 1993) and in the northern countries (Taylor, Walton& Young: 1977), in the debates of critical criminology proper, there is a clear intention to amalgamate the aforementioned theories in order to offer wide interpretation frameworks susceptible of sub-interpretations of enormous diversity. Because this integrative intention of the same critical criminologists, it is possible to identify the previous theories with them. These common frameworks of interpretation consist fundamentally in four visible aspects:

Opposition to positivist theory and epistemology through the epistemological integration of the object relationship (delinquent and delinquency, fundamentally) with the subject (social control system, penal system, criminal science, knowledge-science, socio-economic structure), in addition to other transversal variables (police, gender, victim, white collar, etc.). This integrating vision allowed us to approach a structural knowledge of the criminal phenomenon that opens the doors to previously impertinent questions in criminology, such as: To what extent is the definition of crime and deviance affected by historical, circumstantial and situational structures of power? How are the definition of deviance and delinquent not tautological but the result of a system of social and criminal control? How efficient is the criminal justice system and its inculturation? How criminal justice system responds to stereotypes and needs for social control over the idea of justice? Is there another way to measure justice? (there, it is possible to find measuring references such as liberation, Human Rights, social integration, Constitution, Civil Justice, proximity, limits to power, equality of opportunities, among others).

The notion of "criticality" was taken from the Frankfurt School or Critical Theory, which had allowed to develop a theory of knowledge of greater scope than the hitherto omniscient positivist theory of science. This "greater scope" comes from the integration of the new ideas about subject: iusnatualism, communication, the nature of the scientific, the investigator and the investigation and the investigated facts. To this article purpose, main consequence of this approach would be the possibility of understanding the criminal phenomenon from the theories of power.

Another source common to this criminology, although not always fully consistent with later authors, is thework of Marxians such as Michel Foucault (Foucault: 2015; 2010; 1968). In particular, this author interrogates power and its institutional reflexes as an inseparable part of historically constructed knowledge, in light of prevailing modes of production and epistemic interactions, such as those derived from language. The ideas of deviation and norm, so precious in critical criminology, have their origin in the Foucaultian approach. Some approaches of critical theory suppose, like Foucault, that the structural distribution of knowledge and power in the exercise of justice is an incontrovertible fact within epistemic time, due to the nature of the historical- symbolic structure that gives meaning to the power and its institutional reflexes (Zaffaroni: 2011). Therefore, these approaches are very careful of the use of the term criminal policy (Zaffaroni: 1982). The postmodern impact, which can be somehow complemented by Foucault's idea of structure, also acted in favor of the impossibilitism of criminology, dissolving the centrality of the criminal policies and asking the critical criminology to reflect on the definition of the crime object and social reaction (Erickson & Carriére: 2006; Pavlich: 2006). Other authors, however, are more optimistic: they use Foucault directly or indirectly, adding their theory of power to the reflections of Critical Theory to guide the keys of a criminal policy that integrates social subalternity into the theoretical system, prone to communicative action and, in general terms, allow social and institutional transformation (or/and reform) from its root, in order to generate justice together with the reduction of crime (Baratta: 1999; Aniyar de Castro: 2010; Christie: 1993).

Other optimists, like the leftist realists, drink directly from the Marxian source from which Foucault also drank (Young: 2006; Taylor, Walton & Young: 1977). In the context of this literature much of the basic reflection of critical criminology on modernity is established to date: "the growth of the crime rate, the revelation ofinvisible victims, previously ignored phenomenon, the problematization of the definition, and the growing awareness of the universality of crime and the selectivity of justice " (Young: 2006, pp.84-85).

One of the theories that flowed into critical criminology is abolitionism. In particular, this theory must be referred to understand the problem of consumption tables in Ecuador, since it is directly and indirectly referred by the authors promoting the consumption table in a central way.

4.1. The arguments in favor of the consumption table in the light of critical criminology

-

The evidence described above shows that the approval of a relatively high consumption table, in the Ecuadorian context, led to an increase in criminal activity and related apprehensions, at least, to one of the most dangerous micro-trafficking substances. This directly contradicts the arguments corresponding to the literal e, h and j, since police activity and criminalization processes did increase, precisely, under the influence of the defended table.

The policy of the tables, independently of its intentions, had a clear impact on the increase in police activity throughout the territory and in the number of people apprehended, which would possibly generate higher costs to the prison system, contrary to what exposed in the literal e.

From a critical perspective, it would imply an increase in the social control capacity of the State over society, since the increase in activity brings in response to a greater invasion of the police in the life worlds of citizens. Being that a non-convenient intention to the citizen guarantees is that the crime justice system equals the system of social control (Baratta: 1999; Aniyar de Castro: 2013; 2003; Hulsman & Bernat de Cellis: 1984), the results provoked by the new table are not auspicious.

4.1.2 Criminalization and labeling

As a consequence, if the anti-drug activity, apprehensions, the police presence and, in addition, the territorial control of the criminal undertakings over the small territories grew, as can be seen from the second investigation, it is logical to presume that the policy also contributed to the criminalization of the simple consumer, both in the police-institutional imaginary, and in that of the neighbors. In other words, the arguments corresponding to the literals c, e and f would also be contradicted, as regards the processes of social labeling (Cohen: 1992; Becker: 1970; Aniyar de Castro: 1977).

4.1.3 Labeling and political action

In relation to this angle, the defenders assign rights to the consumer3, as it is understood from literal b, and therefore, it would correspond to protect their "autonomy of their will or free personal development", as it is understood from literal a. But this is a contradiction from two points of view:

First, it is a falsification of the Ecuadorian doctrine, which does not interpret the consumption of illegalsubstances as an act of political freedom, but associated with addiction, which is a public health problem (National Assembly: 2008. Art 364).

Second, by presuming that the consumer's right must be protected because it is an act of political freedom,the consumer is being assigned a political role as an object of oppression and, therefore, a subject of redemption. This is extremely dangerous.

It is true that Becker observed that, by recognizing the labeled subject, it is natural to stand on his side and protect him from symbolically constituted power (Meuser & Loschper: 2002; Becker: 1970)4, but Cohen is very clear in noticing the dangers of confusing a labeled sector with the subject of social redemption:

“Gay liberation, ideological drug users, tenants’ associations, squatters, prisoners’ unions, and more recently mental patients’ unions were calling the tunes. In a real sense these groups were becoming politiziced, and it was (and still is) impossible for any sociologist to avoid trying to make sense of these developments.Equally impossible, however, is to accept the way in which the Brand of the deviancy theory evolved by contemporary “hip Marxists” seized upon these groups and elevated them to the status of political whithout any clear thought about the conceptual problems involved (…)Unfortunately, not only was this approach excessively romantic in conception but –like the radical non intervention model- it carried remarkably few prescriptions that could actually be followed by social workers in any practical sense” (Cohen: 1992, pp.103-104)

Cohen points out to the dangers of thinking on complexity through a mechanic and simplistic etiology. Thus, not always restraining the causes produces consequences disappear.

5. THE DANGERS OF MICRO-TRAFFICKING

Micro-trafficking is not a "minor" evil, as it is understood from literal d. It is an actor-protagonist of the crime in the micro-spaces, which affects in an extended way to almost all the population of the country, above all, in the corresponding urban conglomerates. This is a crucial problem in situational criminology, which gives prominence to a criminal policy, fundamentally preventive, based on micro spaces. Evidence suggests that a small group of people, actors from small territories, are responsible for producing an important part of the reported crimes of an urban conglomerate (Sherman: 2012, p.8; 1996).

In fact, police actions on these microterritories have efficiently "proved" that they can reduce total crimes in several cities of the world by approximately 40%. This even led to the declaration of a "Law of Concentration of Crime" (Weisburd: 2015;Weisburd, Groff & Yang: 2012).

It implies, precisely, one of the most interesting meeting points between situational and much of the critical criminology authors: for them, prevention in small territories is the fundamental criminal policy. Only from the capacities of the institutions and community to understand the focal dynamics of crime, efficient solutions can be implemented for the reduction of crime.

In fact, in abolitionist theory, it is "face to face" or "proximity" communication that would allow more effective conflict resolutions than those promoted by the penal institutions, of which, on the contrary, there is not much to expect (Hulsman & Bernat de Cellis: 1984, pp.75-77).

However, the increase in the criminal problem provoked by the table, represents a vertical and disconnected State intervention, which seemed to generate an imbalance of forces in the small territories, made prevention more difficult and contradicts, for so, the same abolitionist spirit.

6. THE ABOLITIONISM

The last literal to analyze is the i, which refers to the abolitionist position by which all punishment is irrational in itself. According to the argument, the table of high tolerances would be positive. However, this idea must be inscribed in the general definitions of abolitionism to be properly understood.

In the words of Louk Hulsman, the criminal justice system as a whole has proved ineffective in late capitalist ("non-traditional") societies, despite the fact that, in the absence of alternatives, it has a sort of monopoly of legitimacy:

"Now, it is considered that all of them, together [the organs or services of the criminal justice machine], 'administer justice' and 'combat crime'. The truth is that the State’s criminal justice system can hardly achieve such goals. Like all large bureaucracies, it does not primarily aim at external objectives, but towards internal objectives such as: attenuate the difficulties in its interior and grow, find a balance, ensure the welfare of its members, ensure, in a word, its own survival" (Hulsman & Bernat de Cellis: 1984, pp.47-48)

7. IN LIGHT OF THIS, HE SUGGESTS DECRIMINALIZING, DECENTERING AND DE-FORMALIZING

"Whoever pursues or suggests a policy of decentralization and deinstitutionalization is personally encouraged of a much greater confidence in the processes of social regulation that are not formalized or centralized, or less formalized and less centralized. And the reticence with respect to decriminalization is less understandable to him since he perceives the role that the civil legal system could play if, given certain adaptations, the possibilities of such a promotion were possible"(Hulsman& Bernat de Cellis: 1984, p.88)

The abolitionists do not propose simple abolition, but one in which criminal justice and its institutions withdraw to give way to civil justice, that is, a net of alternatives and political and institutional actions that, from the world of social fabrics, give responses to the problems themselves, to the real events that gave meaning to the existence of punishment in the context of their situation. It would be useless to justify decriminalizing large grammage of drug tenure if this do not lead to society generating, in an interpersonal or institutional manner, alternatives to the problems posed. Therefore, the simple criticism of punishment or penalties is insufficient in itself, as stated in literal

The denunciation made by the abolitionists of the ineffectiveness or irrational cruelty of penalties is notintended simply to get rid of them but, in terms of the same author cited by the defenders of the table, to warn about the dangers of a society that does not find different means to solve their problems but through excessive means, such as punitive inflation:

“Nothing said here means that protection of life, body and property is of no concern in modern society. On the contrary, living in large scale societies will sometimes mean living in settings where representatives of law and order are seen as the essential guarantee for safety. Not taking this problem seriously serves no good purpose. All modern societies will have to do something about what are generally perceived as crime problems. States have to control these problems; they have to use money, people and buildings. What follows will not be a plea for a return to a stage of social life without formal control. It is a plea for reflections on limits.” (Christie: 2017, p.3)

Abolitionism, as can be identified, is not an enemy of public policy or civil justice. It leads one to think that decriminalization should not be synonymous with isolated actions. It must involve processes ofdecentralization and deformalization of concrete actions. Abolitionism does not welcome State decisions from the distance, which do not address the real situation where problems occur. On the contrary, it tends to "face to face" or "proximity" solutions (Hulsman & Bernat de Cellis: 1984, pp.75-77).

In the context of the economic pressure generated by poverty and the specific Ecuadorian criminal enterprises associated with micro-trafficking, it is more coherent to propose, for example, a system of assisted legalization of consumption and of other chains of the market of illegal substances. In other words, it would be more coherent with abolitionism to propose the legalization of substances, preparing the empirical, participatory, horizontal and situational foundations for this, instead of vertically acting on a small and isolated part of the problem.

8. CONCLUSIONS

The tenure table, designed with the intention of tolerating consumption, contrary to what its designers intended, produced undesirable effects in the increase of illicit activities of drugs, more apprehensions, and a conflictive territorial control of criminal enterprises in small territories of Ecuador. As a consequence, it is possible to estimate an increase in labeling criminalization, greater vulnerability of citizen guarantees of consumers and a greater associated presence of the police at the civil fabrics.

These results are contrary to the premises of critical criminology, whose theoretical framework was usual in the justifications of the same defenders of the tables.

From the situational perspective, the tenure table introduced other problems: It allowed a consumption of10 to 20 personal doses per day, without contemplating the possibility of mixing drugs, while completely prohibiting the cultivation, transportation and the market for the same substances. This situation is produced in a country which borders are permeable of the larger amounts of drugs for export in the world, which northern border is noise-to-noise near of important production centers generating residual products, susceptible to micro-trafficking at an attractive price in domestic market. This situation generated the opposite effect to desired: The tenure camouflaged the domestic traffic and became an unwanted escape valve for the economic pressure generated by the drug business inside Ecuador. The situation allowed the criminal opportunity.

In simple words, a lesson can be harvested: before implementing the policy, it is a priority to diagnoseadequately, understand the criminal situation and stick to it. Since the child wanted to put his finger in the plug, it was simply necessary to prevent him from doing so (blocking the plug, changing the wiring, lowering the system), before the accident.

This approach is not at all contrary to critical criminology, and has been warned by some of its most important founders, fundamentally in the so-called left realism:

"(...) To that end, it was proposed as necessary to work at the theoretical level, at the level of empirical research and at the level of concrete policies (...) At the academic level, empirical studies must be developed that are well-founded, to break the current trend of an a-theoretical empiricism and an a- empirical theory (...) The reforms of the criminal justice system were fundamental to raise the struggle for the 'law and order'. For this reason, they would be especially concerned with the study of police strategies" (Anitua: 2010, p.448).

It is evident that critical criminology, in its lax sense, has very different angles, which do not end in left realism. Some of these angles leave in the shade the centrality of the crime problem to refocus the social reaction and the reflections of power. It is even possible to think that critical criminology decentered crime reduction, as it has been discussed and has been proposed (Pavlich: 2006). But we stand with Sozzo that it is not possible to say that the reduction of crime is not a fundamental problem of critical criminology, in any ofits trends (Jiménez & Santos: 2016, p.46-50). This simple premise, seems to entail the obligation of a criminology oriented to empirical evidences about the dynamics of crime, both to reduce it and to indicate the perversions of the social reaction and its institutions:

"One of the challenges of intellectual production in this field of knowledge [critical criminology] is to generate that encounter with the empirical moment, not to reconcile with the existing state of things, but to question the dynamics of production of the state of existing things in a level that has the necessary precision so that the actors recognize themselves in their roles and in the described effects, and in the actors with whom they can -which are not always all-, create awareness and action to resist to some of the perverse dynamics of these institutions " (Jiménez & Santos: 2016, p.47-48)

With this example, we argue in favor of the need in Latin American criminology to turn the regard towards an empirical perspective, respectful of the meaning of the situation and the criminal opportunity, that allows us to integrate the evaluation of the specific context of the victim, the stable formulation of criminal policies centered in the reduction of crime and justice in an extended way, as well as the protection (and expansion) of civil guarantees. This is not contradictory to recognizing the structural sources of power and social control that determine the selectivist nature of the crime justice system.

BIODATA

Daniel CASTRO-ANIYAR: Sociologist (LUZ), Anthropologist (U de Montreal, EHESS Paris), DEA in Public Policies (UCM) PhD in Conflict and Peace Process (UCM). Professor of criminology and method at ULEAM (Ecuador). Researcher in CEPSAL (Venezuela /Ecuador) and GIGPP (Venezuela/Ecuador/Colombia). Advisor of the Ecuadorian National Police.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ANITUA, G.I. (2010). Historias de los Pensamientos Criminológicos. Ediar. Buenos Aires.

ANIYAR DE CASTRO, L. & CODINO, R. (2013). Manual de Criminología Sociopolítica. Ediar. Buenos Aires

ANIYAR DE CASTRO. L. (2010). Criminología de los Derechos Humanos. Criminología Axiológica comoPolítica Criminal. Editores del Puerto. Buenos Aires.

ANIYAR DE CASTRO. L. (2003). Resumen Gráfico del Pensamiento Criminológico y su Reflejo Institucional. Ediciones Nuevo Siglo. Mérida

ANIYAR DE CASTRO. L. (1977). Criminología de la Reacción Social. Instituto de Criminología. Facultad de Derecho. Universidad del Zulia. Maracaibo.

Asamblea Constituyente (2008). Constitución de la República del Ecuador. Constitución de bolsillo. Asamblea Nacional. http://www.asambleanacional.gov.ec/documentos/constitucion_de_bolsillo.pdf

BARATTA, A. (1999). Criminologia Critica e Crítica do Direito Penal. Introducao a Sociologia do Direito Penal.Instituto Carioca de Criminología. Colecao Pensamiento Criminológico. Freitas bastos Editora. Rio de Janeiro.

BARATTA, A. (1999) ‘Fundamentos Ideológicos de la Actual Política Criminal sobre Drogas. Reflexiones Alrededor de la Teoría del Poder en Michel Foucault’. Kosovswi, Ester (coord.) Vitimologia. Enfoque Interdisciplinar. Sociedade brasileira de vitimologia. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro.

BECKER, H. S. (1970). ‘Whose Side are We on?’ Jack D. Douglas (Ed.) The Relevance of SociologyAppleton-Century-Crofts. New York.

CABARCA, S. (2018). ‘Pertinencia de la Tabla Ecuatoriana de Tenencia de Substancias Ilícitas desde el Principio de Integralidad de la ‘Salud Pública’’. Revista Espacio Abierto. Forthcoming.

CASTRO ANIYAR, D. (2015). Especialización en Territorialización Simbólica, Etnografía y Situación Criminógena Aplicado a Políticas Criminales. Informe Final Prometeo. Ministerio del Interior/Senescyt. Quitohttp://repositorio.educacionsuperior.gob.ec/bitstream/28000/4691/3/Anexo%203.%20Informe%20t%C3%A9 cnico%20resumen%20ejecutivo.pdf

CASTRO ANIYAR, D. (2018). “Los Mapas Cognitivos Compuestos: Una respuesta a problemas general de medición del delito” in Castro Aniyar, D. (edit.) Leccionario de Derecho Fundamental y Criminología. Ediciones Uleam. Manta.

CHRISTIE, N. (2017). Crime Control as Industry. Towards Gulags, Western Style. Routledge. London, New York.

CHRISTIE, N. (1982). Limits to Pain. Martin Robertson. Oxford.

COHEN, S. (1992). Against Criminology. New Brunswick, London: Transaction Publishers

CONSEP (2015). Resolución 001-CONSEP-CD-2015. CONSEP Quito: Prevención Drogas. http://www.prevenciondrogas.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Resolución-No.-001-CONSEP-CD-2015- de-9-de-septiembre-de-2015.pdfDirección Nacional Anti-Drogas, Subsecretaría de Seguridad Interna del Ministerio del Interior, Departamento de lucha contra las drogas, Proyecto Prometeo & Senescyt (2015). Informe Análisis Integral de la Tabla de Consumo Vigente en Registro Oficial Nro. 19-2013. Ministerio del Interior. Policía Nacional del Ecuador. Senescyt. Quito,

ERICKSON, R. & CARRIÉRE, K. (2006). ‘La Fragmentación de la Criminología’. Sozzo, Maximo (coord.)Reconstruyendo las Criminologías Críticas. Edit Ad Hoc. Buenos Aires.

FOUCAULT, M. (2015). La Verdad y las Formas Jurídicas. Gedisa editorial. Serie Cla-De-Mah. Barcelona

FOUCAULT, M. (2010) Vigilar y Castigar. Nacimiento de la Prisión. Siglo XXI Editores 13va edición. BuenosAires.

FOUCAULT, M. (1968) Las Palabras y las Cosas. Una Arqueología de las Ciencias Humanas. Siglo XXI Argentina Editores 3era edición. Buenos Aires.

HULSMAN, L. & BERNAT DE CELIS, J. (1984). Sistema Penal y Seguridad Ciudadana: Hacia una Alternativa. Ariel Derecho. Barcelona.

JIMÉNEZ, M.A. & SANTOS, T. (2016). ‘De la Criminología Critica Actual y cómo el Populismo Penal Deslegitima a la Justicia y sus Procesos de Reforma. Entrevista a Máximo Sozzo’. Nova Criminis: Visiones Criminológicas de la Justicia Penal. Vol. 7, No. 11. Universidad Central de Chile. Santiago.

MEUSER, M. & LOSCHPER, G. (2002). ‘Introduction: Qualitative Research in Criminology’. FQS Journal.Volume 3, No. 1, Art. 12. January 2002. Freie Universitat Berlin

Ministerio del Interior (2015). Análisis Situacional y Propuestas de Reforma. Tablas de Cantidades Máximas de Estupefacientes para Consumo Personal. Informe ante el CONSEP. Quito.

ONUDC (2017). Monitoreo de Territorios Afectados por Cultivos Ilícitos 2016. Julio 2017. ONUDC-Gobierno de Colombia. http://www.biesimci.org/Documentos/Documentos_files/Censo_cultivos_coca_2016.pdf

ONUDC (2015). Indicadores de Cultivos Ilícitos en el Ecuador 2014. Octubre https://www.unodc.org/documents/peruandecuador//Informes/ECUADOR/ecuador_2015_Web_2.pdf

PALADINES, J. (2017). Matemáticamente Detenidos, Geométricamente Condenados: La Punitividad de los Umbrales y el Castigo al Microtráfico. ILDIS. Friederich Ebert Stiftung Ecuador. library.fes.de/pdf- files/bueros/quito/13411.pdf

PALADINES, J. (2015). Nuevas Penas para Delitos de Drogas en Ecuador: ‘Duros Contra los Débiles y Débiles contra los Duros’ TNI. Proyecto Drogas y Democracia. 08 de octubre. https://www.tni.org/es/artículo/nuevas-penas-para-delitos-de-drogas-en-ecuador-duros-contra-los-debiles-y- debiles-contra

PALADINES, J. (2015a). ‘Drogas, Policía y Democracia: Retos para una Nueva Agenda Política’. Revista Defensa y Justicia. 04 de Diciembre. Quito: Defensoría Pública.

PALADINES, J. (2013). Ni Enfermos ni Delincuentes. Acerca de los Umbrales para el Uso de Drogas Ilícitas. Asociación Pensamiento Penal. 26 de Julio. http://www.pensamientopenal.org.ar/jorge-vicente-paladines-ni- enfermos-ni-delincuentes-acerca-de-los-umbrales-para-el-uso-de-drogas-ilicitas/

PAVLICH, G. (2006). ‘Crítica y Criminología: En Búsqueda de Legitimación’. Sozzo, Máximo (coord.)Reconstruyendo las criminologías críticas. Edit Ad Hoc. Buenos Aires.

Redacción Seguridad (2017). Jorge Paladines: El Diálogo por las Drogas Debe Incluir a las Familias, a Técnicos…. Diario El Comercio. 7 de Julio. http://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/jorgepaladines-dialogo- nacional-lucha-antidrogas.html

SHERMAN, L. (2012). Developing and Evaluating Citizen Security Programs in Latin America. Cambridge University. University of Maryland. Inter-American Development Bank. Technical Note IDB-TN-436. Institutions for Development (IFD), in http://www20.iadb.org/intal/catalogo/PE/2012/11273.pdf

SHERMAN, L.W. (1996). ‘Policing for Crime Prevention’ in Sherman et al. Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesn't, What's Promising. A Report to The United States Congress. Prepared for the National Institute of Justice. University of Maryland, in https://www.ncjrs.gov/works/chapter8.htm

TAYLOR, I., WALTON, P. & YOUNG, J. (dirs.) (1977). Criminología Crítica. Siglo XXI editores. Nueva criminología. México.

WEISBURD, D. (2015). ‘The Law of Crime Concentration and the Criminology of Place’. Criminology. Vol. 53. Num. 2, pp 133-157.

WEISBURD, D.; GROFF, E. & YANG, S. (2012). The Criminology of Place. Street Segments and our Understanding of the Crime Problems. NY: Oxford University Press.

YOUNG, J. (2006). ‘Escribiendo en la Cúspide del Cambio: Una Nueva Criminología para una Modernidad Tardía’. Sozzo, Maximo (coord.) Reconstruyendo las criminologías críticas. Edit. Ad Hoc. Buenos Aires.

ZAFFARONI, R. (1982). Política Criminal Latinoamericana. Perspectivas-Disyuntivas. Editorial Hammurabi. Buenos Aires

ZAFFARONI, R. (2011). Estructura Básica del Derecho Penal. Ediar. Buenos Aires

Notes