Tradução

Portuguese colonialism and Angolan resistance in the memoirs of Adriano João Sebastião (1923 - 1960)

Colonialismo português e resistências angolanas nas memórias de Adriano João Sebastião (1923-1960)

Portuguese colonialism and Angolan resistance in the memoirs of Adriano João Sebastião (1923 - 1960)

Revista Tempo e Argumento, vol. 8, no. 19, pp. 439-461, 2016

Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International.

Received: 12 June 2016

Accepted: 31 August 2016

Abstract: This article discusses the greater presence of Portuguese colonialism in the Angolan countryside in the first half of the 20th century and the resistance to it. To do this, we follow a part of the life of the politician Adriano João Sebastião from his birth, in 1923, to his arrest, in 1960, through the analysis of his memoir book Dos campos de algodão aos dias de hoje [From the cotton fields to the present day], published in 1993. Thus, we aim to grasp how Portuguese colonialism affected the daily life of an Angolan man.

Keywords: Angola, Colonization, Resistance, Adriano Sebastião, Memoirs, biographical .

Resumo: Este artigo apresenta uma discussão sobre a maior presença do colonialismo português no interior angolano na primeira metade do século XX e as resistências a ele. Para tanto, acompanhamos parte da vida do político Adriano João Sebastião desde seu nascimento, em 1923, até sua prisão, em 1960, por meio da análise de seu livro de memórias Dos campos de algodão aos dias de hoje, publicado em 1993. Pretende-se, dessa forma, entender como o colonialismo português afetou o cotidiano de um homem angolano.

Palavras-chave: Angola, Colonização, Resistência, Adriano Sebastião, Memórias.

To cite this translation:

NASCIMENTO, Washington Santos. Colonialismo português e resistências angolanas nas memórias de Adriano João Sebastião (1923-1960). Revista Tempo e Argumento, Florianópolis, v. 8, n. 19, p. 439 - 461. set./dez. 2016. Original title: Colonialismo português e resistências angolanas nas memórias de Adriano João Sebastião (1923-1960).

Portuguese colonialism and Angolan resistance in the memoirs of Adriano João Sebastião (1923-1960)

This article aims to discuss Portuguese colonialism and the various forms of resistance to it in the Angolan rural universe in the first half of the 20th century. To do this, we follow a part of the life of Adriano João Sebastião (or Kiwima, as he was also known), from his birth, in Bengo (1923), to his action and arrest in Uíge, in 1960. Sebastião had a close experience of forced labor in cotton plantations and later in the hinterland of Luanda, as a public official, he witnessed fishing exploration and the early resistance articulations between fishermen in the Cacuaco region.

In this article, we use his memoirs, regarded as a ‘collective memory,’ within a specific social framework, i.e. anticolonial resistance, thus serving as an element of social cohesion and construction of a narrative for the Angolan nation[1]. In spite of the collective dimension, they also have an individual dimension, in two senses: the first, Sebastião’s wish to tell his life to his relatives; and the second, the attempt to preserve (or reserve?) his place in the Angolan history through memoirs on resistance to Portuguese colonialism and the construction of a discourse that places him at the birth of the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA), in addition to bringing him closer to one of the most significant African political activists, Amílcar Cabral.

Even though this is a collective memory, it is worth noticing that Sebastião was an exception in Angola. In an environment with more than 90% of illiterates, he managed to gain access to formal education and also belonged to the colonial civil service.

Before going deeper into the analysis of his life story, we discuss the greater presence of the Portuguese colonial apparatus, especially after World War I, in various zones of the Angolan countryside, highlighting the profound social and economic changes within this period and the consequent intensification of tensions that led to the beginning of the anticolonial war, in 1961.

Portuguese colonialism and the occupation of the Angolan countryside

The European weakness caused by the two world wars (1914-1918 and 1939-1945) and the Great Depression (1929) led the Portuguese dictator António Salazar to resort to the potentialities of his African colonies to ensure the Portuguese budget balance, thus promoting a series of economic integration policies and the effective occupation of territories with a white metropolitan population. Salazar changed the politics of the Republic (1911-1926), characterized by administrative and financial decentralization of the colonies, by a rather centralizing model which had greater economic development, especially in Angola[2].

Coffee export, diamond mining, cultivation of sugarcane, oilseeds, and cotton, and trade in timber and other mineral products, such as oil and iron, have made Angola one of the most profitable Portuguese possessions In Africa, above all using local compulsory (and cheap) workforce[3].

A series of obligatory agricultural crops, such as cotton and coffee, were implemented in the countryside, making the lives of Angolan natives even harder, because they were forced to abandon the cultivation of food crops, which left them in a situation of greater vulnerability in times of drought and inclement weather.

These spaces were served by an extensive railroad and highway network, which aimed to allow the goods to reach the international market, through the construction of routes that advanced longitudinally into the countryside, thus connecting the far ends of the colony to the coast[4]. The expansion of the railroad and highway network stimulated peasant production in the regions and their surroundings and the emergence of a job market, since for their construction there was a need to organize workers with some degree of specialization, hired from the native population.

Railways and the new roadways brought from the countryside to the coast the raw materials that would supply the international market. The African (or ‘gentile,’ in the Portuguese terminology) pathways, although disqualified, continued to be used. Maria Emilia Madeira dos Santos (1998) stresses that, because in many cases the ‘official’ roads took a long time to be built, the ‘gentile’ roads were key, since they established links in the vertical way (north-south) and, according to her, “[...] ensured that secular relations were maintained or allowed the old African ethnic groups to keep some cohesion across both sides of a border formed by concrete frames” (SANTOS, 1998, p. 508). These routes constituted a large network that extended in multiple ways from an organization that obeyed the very Angolan rationale, only comprehensible for the natives and a few initiates, something which put at risk the geopolitical interests of Portugal to build in Angola a road network highlighting the spaces already controlled or still to be controlled[5].

This road network crossed the territories of native populations, pushing the Portuguese ‘civilization’ forward and de-structuring local political, social, and economic organizations. The major changes took place among the Bacongos-Quikongos, mbundu-Quimbundu, and Ovimbundu-Umbundu, which were located in the central zones and in northern Angola, regions with greater Portuguese penetration and occupation.

Thus, in the mid-20th century, Portugal had already completed a cycle that redefined a new economic and social scenario for Angola, characterized by extensive production in large plantations and de-structuring of African societies both in rural and urban areas[6]. How these populations felt such an impact and how the latter changed the daily life of Angolans is what we address through the memoirs of Adriano Sebastião, Kiwima.

Adriano João Sebastião, Kiwima (1923-2010): biographical notes

Son of João Sebastião Kiwima and Isabel Jerónimo, Adriano João Sebastião, or Sebastião Kiwima (a reference to his father), was born in Calomboloca, an area within the commune of Cassoneca, a province in Bengo, on August 11, 1923, a region of large production of cotton and strong Portuguese presence, and he migrated, on April 22, 1938, to Luanda, in order to complete his education.

After graduating from the 2nd Level (4th grade), in 1939, he was invited by the Director of the Escola da Missão, Ms. Elisa Klebsattel, to teach as an assistant teacher that year. Over the years, he was a teacher and a civil servant. He married Hermengarda Paulo de Almeida Sebastião in 1951, with whom he had 4 daughters, Isabel Dulce de Almeida Sebastião (Tinha), Luzia Bebiana de Almeida Sebastião (Gy), Ana Paula de Almeida Sebastião, and Adriana Stella de Almeida Sebastião (Didi).

He was one of the founders of the Partido de Luta Unida por Angola (PLUA), in 1956, and in 1960 he joined the boards of the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA), being a member of its first executive committee in Luanda. Arrested in the year 1960, he was a prisoner from 1961 to 1967.

After the Angolan independence, in 1974, he took up administrative and political positions in the new independent government, being for some years ambassador of Angola in Portugal (1978 to 1982). He published two memoir books, Dos campos de algodão aos dias de hoje [From the cotton fields to the present day] (1993) and Missombo (2012). Adriano João Sebastião died in 2010, in Luanda, at the age of 87 years.

The memoir book Dos campos de algodão aos dias de hoje is divided into 13 chapters ranging from life in the Angolan countryside and migration to Luanda to his rise within the post-independence Angolan State. To a large extent, it depicts various dimensions of anticolonial resistance in the 1940s and 1950s, in the rural region of Calomboloca, Cassoneca, and Catete, and generally in the province of Icolo and Bengo.

In this work, there is Sebastião’s concern to detail genealogies and names that he regards as important for his history. Amadou Hampaté Bâ (2012), although referring to the traditions of the savannah region south from the Sahara (especially Mali), helps us seeing Sebastião (1993) as a genealogist, a quality that is expressed mainly in the first chapter, “Kalomboloca 1932–38,” where he constructs the genealogies of the oldest families in his region of origin. Hampaté Bâ (2012) claims that genealogy is a feeling of identity and a way of honoring the family glory. Sebastião (1993) can also be seen in the sense assigned by Jacques Le Goff (2003) as a ‘memory man,’ i.e. individuals of predominantly oral societies who are the ‘genealogists’ and traditionalists in that society. They are the ‘society’s memory,’ at the same time custodians of ‘objective’ history and ‘ideological’ history[7].

Dos campos de algodão... had been constructed for his daughters, in order to ‘report’ and ‘tell,’ “[...] where we came from, what we heard and did until the moment we wrote it” (SEBASTIÃO, 1993, p. 132). In this way, Sebastião’s memoirs, besides the discourse for himself and the others (collective memory), also have an intermediate dimension, the acquaintances. According to Paul Ricoeur (2007), the “[...] acquaintances, these people who tell us and those we tell to, are situated within a range of distances in the relation between the self and the other” (RICOEUR, 2007, p. 141). Thus, Sebastião’s narrative is also a discourse for his later generations.

The book begins with a reference to the ancestors citing 80 names of the ‘elderly’ in the region. It also states that this was the region where the writer Uanhenga Xitu, his cousin, lived. And it points out that one of the most emblematic characters in the Angolan literature, Master Tamoda, created by Xitu, had in fact existed and lived in the region:

He was Kamoda and not Tamoda. His full name was: Jorge António Kamoda, a native of Kionzo. He came to Kalomboloca with his brother António Soares or brought by his aunt Luiza Antônio (Kangulu Kathoni) after his mother’s death and because Luiza Antonio was a friend of the Fortunato family. They were little kids and grew up in Kalomboloca. (SEBASTIÃO, 1993, p. 18)

Kamoda could have become a farmer, but ‘very clean, so clean and neat’ that after a day’s work on the hoe he dressed completely in white, denim shorts, half-sleeve shirts, white shoes, high socks, and a helmet. The name Tamoda might be a variation of Kamoda, a jocular nickname that means, in Kimbundu, a fashion man. He walked with a Portuguese dictionary in his hands explaining to anyone who asked him a few words in Portuguese, thus he was treated in a discriminatory manner[8].

The Kamota/Tamoda’s account of history shortly after the description of the ‘elderly’ serves, on the one hand, to show the importance of that region, in face of such a significant character of the Angolan literature and, on the other, it criticizes the association of natives with the models imposed by the colonizer. After this, Sebastião started discussing the cotton plantations between 1932 and 1938, in Calomboloca, in the province of Bengo.

The cotton fields in Calomboloca

The region is described by Sebastião (1993) as a large cotton producer with a strong Portuguese and missionary presence. According to him, his childhood in the 1930s was a period of much violence, due to his parents’ poverty, feeling troubled by the Kimbares and representatives of the Portuguese administrative authority in the location, as well as by the village sobas, being forced to make the first forced labor to repair the road linking Luanda to Malanje[9].

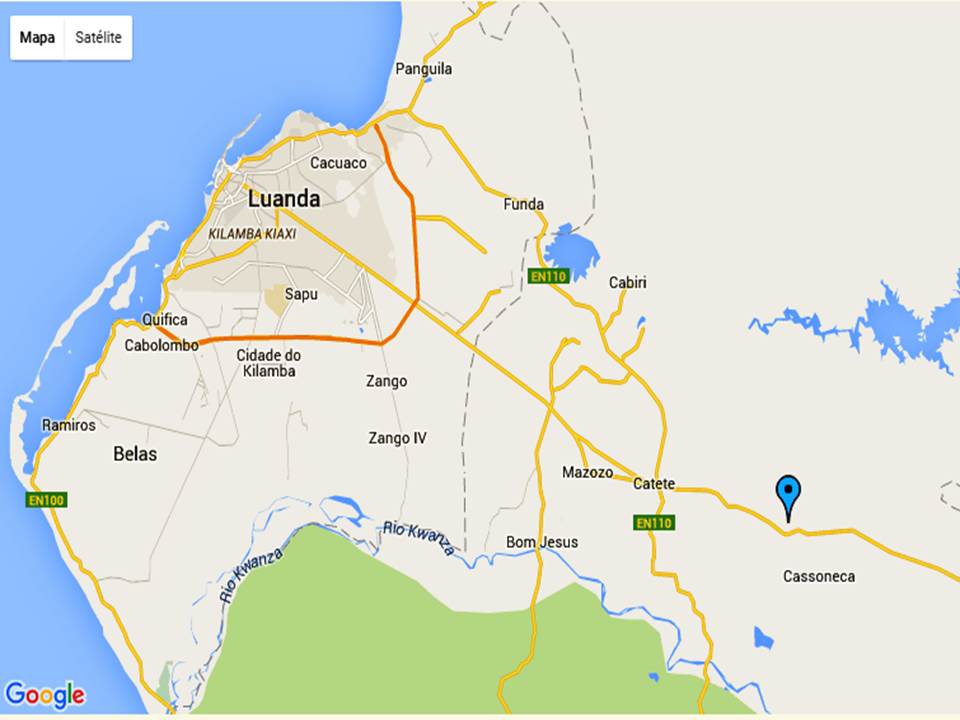

Image 1

Calomboloca (marked with a blue symbol)

Source: http://www.maplandia.com/angola/bengo/icolo-e-bengo/calomboloca/

According to the Estatuto do Indigenato (1926-1961), a set of Portuguese laws designed to ‘organize’ and ‘control’ its colonies, forced labor was stipulated for all African males, between 19 and 55 years, who did not have any type of disability and worked by employing their services to others[10]. Just as they had no way to pay taxes through their own products, the administrative authorities legally recruited them, over 6 months for compulsory labor[11]. In the account by Sebastião (1993), we can see that the minimum age of recruitment was illusory, since at 10 years old he was taken to compulsory labor:

In fact, my father’s poverty was such, in monetary terms, that I did not have money to give the Kimbares when they appeared to nominate for the road service, so that I still engaged in two campaigns of these services for three weeks each and the utmost and last took place in 1933, when I was 10 years old, when the Kimbar António Afonso appeared in the dead of night, to get me out of my mother’s bed, in order to go to Cabiri, as an employee of the Cotton Field owned by Carlos Jorge, the kipuka, for the cotton campaign over six months. My father could do nothing and my mother much less, then I went. (SEBASTIÃO, 1993, p. 25)

Cabiri, a region referred to by Sebastião (1993), is a rural settlement in the municipality of Icolo and Bengo[12]. In the mid-20th century, it was known for its large cotton production and the installation, in 1962, of a settlement of immigrants from the Cape Verdean islands of Morabeza[13].

Regarding forced labor in Angola, using colonial indicators, Solival Menezes (2000) claims that between the years 1935 and 1939 the metropolitan government used 720 thousand people per year[14]. According to him, most of these employees were concentrated in two coffee producing regions, Cuanza Norte and Uíge, although they were immigrants from Huambo and Bié, a predominantly Ovimbundu region[15]. Concerning the daily life in the cotton fields, Sebastião (1993) says:

In Kipuka, to be free of the spanking paddles which the employees underwent, everyone had to fill three cotton bags that were worn to weigh between 80 and 100 kg. As I was a little person, I could not fill the three bags, so that the first three weeks consisted in spanking paddles every other day until the oldest Dean, my fellow from the sanzala and others who I did not know decided to help me by filling two of my bags because I could fill only one. (SEBASTIÃO, 1993, p. 25)

The use of punishment in forced labor was common in the Portuguese empire and it was justified by the metropolitan authorities that asserted that an ‘Indian’ would not fear so much imprisonment, but immediate corporal punishment[16]. Associated with excessive corporal punishment, long working hours and poor housing and food conditions led these workers to often establish relationships based on solidarity and escape strategies[17].

According to Claudia Castelo (2007), the very management of Indian business services recognized that in many cases corporal punishment due to insignificant faults was recurrent, drawing attention to the need to make them more ‘paternal,’ “[...] just as, by the way, people used to do for a long time at schools, and even in the family, provided that it is applied moderately, consciously, and humanely” (CASTELO, 2007, p. 287).

In addition to corporal punishment, another way instituted by the colonial administration to spread fear through suburban areas in the municipalities or rural settlements was the practice of so-called ‘spats,’ a kind of police diligence, to arrest people considered as ‘disorderly,’ alleged suspect place-goers, and above all those who did not bring obligatory documents (the Indian booklet) or those who were regarded as idlers, contract breakers, etc.[18]

The large number of escapes worried the Portuguese authorities, as well as the Portuguese intelligentsia. Afonso Mendes (1958), referring to this situation in his research on Huíla and Moçamedes, comments that “job abandonment by Indian workers takes a remarkable transcendence in the Angolan economic system” (MENDES, 1958, p. 72). He points out that often ‘contracts’ were broken by more than 90% of the workers who simply fled the labor fields. Just as Sebastião (1993) did:

After a month and two weeks the oldest Dean thought this situation was so unbearable that he could not take it any longer and decided that we should flee. And if he thought better of it, we would put it into practice before we were discovered, because in places of martyrdom like this there is never a lack of people who collaborate with the guards [...] In the dawn of a day, I cannot recall if it was Monday or Tuesday, but it seemed to be Monday due to the time we walked, only at night, because during the day we had to hide in the grass so that we were not caught before the morning call for checking the staff, the oldest Dean and I fled from Kipuka towards Mbanza Kitele and we sheltered in Adão Bernardo’s house. (SEBASTIÃO, 1993, p. 26)

Faced with the situation classified as ‘unbearable’ and even before the possibility of being denounced by other Africans, he managed to escape, but besides putting his life at risk, exposed his mother who, unaware that his son had fled, went to the cotton field to visit him. Realizing the situation, Sebastião’s mother also decided to escape:

[...] and as my mother told us after having butterflies in her stomach, i.e. painful belly skin due to dragging herself so much, she decided to stop and get into a hole she found to rest and because it was already night, she chose to sleep in that hole and still heard, because the wind blew in that direction, the guards saying: If we catch them..., the son of a bitch was lucky that his mother... our dogs would tear her skin and eat her – a. (SEBASTIÃO, 1993, p. 26)

In this account, Sebastião (1993) depicts the image of the Portuguese colonial system marked by violence that, with the collaboration of African guards, did not set aside either women or the elderly. Days later, they found his mother and came back to Calomboloca, where they took refuge in a plantation. After about a month, they were discovered by ‘kimbar’ (name given to the Angolan guard) who did not care much, unlike the local soba, Kaioho de Nganga zuze (from the Portuguese name Manuel da Costa Fernandes)[19].

Elisabete Silva (2003) says that these sobas were not incorporated into the formal system of colonial administration, but they were indispensable instruments for a successful Portuguese colonization in Angola; however, not everyone became a soba in that scenario of Portuguese colonization, since Portugal overthrew rather rebellious traditional local authorities and replaced them with rather collaborative leaders, who acted in partnership with the ‘office centuries,’ heads of agropastoral political units where the institution of hereditary heads did not exist[20]. Being afraid of some attitude of the local soba, and to prevent that something bad could happen to Sebastião, his mother sent him to the school at the protestant mission of Icolo and Bengo, administered by Shepherd Cristóvão Agostinho de Carvalho.

In the history constructed by means of his testimony, some common traits of Angolan life that he sought to denounce: colonial exploitation associated with forced labor and physical violence, commitment and collaboration that local native authorities often agreed with the colonizer; escape as an act of resistance, and finally education within the Protestant missions[21].

The fact he had access to the colonial school enabled Sebastião to move to Luanda years later (in 1938), after finishing the second grade. In Luanda, he was able to keep studying and became a teacher in the capital for classes at the first and second grades (years), a position that he could exercise provisionally and for a few years (1940-1947), having tendered and being admitted as a public official shortly after (1948).

Trade in fish in Cacuaco and the beginning of political action (1948-1958)

After working as a teacher at the Missão Metodista de Luanda, Sebastião passed a public service entrance exam and took the position of Fiscal Cobrador dos Mercados, and despite being ranked in first place thus gaining the right to work in the Mercado Principal de Luanda, he was sent to another, also in Luanda, but far from downtown, the Cacuaco market. “The Cacuaco market competed for the applicant ranked in third place, but a black man could not be among the white men, otherwise he might stain them with his color, he had to be away, so his place was Cacuaco and we went there” (SEBASTIÃO, 1998, p. 54-55). Sebastião remained in Cacuaco for ten years (1948–1958), being later moved to the Ingombotas in Luanda.

Image 2

Cacuaco (with a slight red highlight)

Source: https://www.google.com.br/maps/place/Cacuaco,+Angola

Cacuaco was described by Sebastião (1993) as the most important fish production location in the sea along the Luanda coast. According to him, the best shrimp on the coast came from there, as well as a diversity of fish species, taken through dragging nets and trawls by local native fishermen. When he arrived in the year 1948, there was only one white man in the locality, who was called Martins Latagaio and bought all fish from the local fishermen, working as a middleman. Over the years, the same Portuguese man ordered the production of his own nets, hired fishermen, and also started fishing, but kept buying fish from others. Since the 1950s, ‘other white men’ began arriving to negotiate with local fishermen.

In 1958, a metropolitan law prohibited fishing on the high seas without using motor boats, more expensive and belonging to the Portuguese men. This act made it even more difficult for native fishermen. Américo Boavida (1967) says that the aim would be “[...] putting Africans overnight in the situation of wage earners of European fishermen. Through this decree, the last independent sector of the traditional African economy disappeared!” (BOAVIDA, 1967, p. 49). Despite the exaggeration of this statement, it is a fact that the native fishing industry declined and this led fishermen to seek ways to associate to resist colonialism.

It is precisely in this context that Sebastião begins his political activity, especially in contact with Manuel Bento, a nurse from Cassoneca, Icolo-Bengo, the same region of Sebastião. Bento was one of those responsible for bringing him the situation of the Angolan countryside; during long conversations at dawn, he reported the harshness of coffee plantation cleaning and coffee harvesting, coffee bag work, exhaustive work, and the fact that the employee cannot be ill, despite being affected by scurvy, a disease caused by precarious eating, besides:

[...] often the employees were taken to the administrative office to be beaten with paddles due to no valid pretext only to instill respect and above all fear of the white men who must be blindly obeyed: an employee or a black man had to see a white man as almighty, infallible, and fair whenever addressing a black man because the latter was only a slothful, sly, gentile, mumbo-jumbo who had to be educated in order to obey and this could be achieved only with a blow that did not exclude death. (SEBASTIÃO, 1993, p. 67)

According to Bento’s account, Sebastião (1993) also registers racism practised by white men against black men and that the “[...] black fisherman from there could never know himself and his value as an element of society if he was not prepared and if he did not learn to read” (SEBASTIÃO, 1993, p. 68). From then on, even being a Protestant, he began to articulate along with local priests so that in this region a school could be open.

At this moment, he also makes contact with the Partido da Luta Unida dos Africanos de Angola (PLUAA), starting to create clandestine cells to spread the organization and organize actions of resistance to Portuguese colonialism. In practice, they should sabotage the fishing activity of white men by making large holes in their fishing nets, thus boycotting the activity. In addition to encouraging fishermen to unionize and demand better wages, relying on the aid of Domingos António Lopes, Alexandre Agostinho, and António Diogo da Silva. The early group was joined by Antonio Jacinto do Amaral Martins (A.J.) and Mario Antônio Fernandes de Oliveira (M.A), who arrived in the region in the year 1955[22]. These actions resulted in the founding of the Cooperativa dos Pescadores de Cacuaco, which started organizing local workers.

The presence of Amílcar Cabral in the Angolan countryside

It was in Cacuaco that Sebastião met one of the main anti-colonial militants in the African continent, the Guinean man Amílcar Cabral, when the latter arrived in the region in 1955. Cabral was in Angola between 1955 and 1958 working as an agronomist engineer in three farms, Cassequel, Tentativa, and São Francisco and developing a series of cartography and recovery activities aimed at salty soils[23].

His public mission was studying soils in the Dande region, especially in the farm Tentativa, but in practice he established clandestine networks of resistance to the Portuguese government, thus he already had information about Sebastião, perhaps provided by Deolinda Rodrigues de Almeida or Noé da Silva Saúde, major figures of the anticolonial fight, with which Sebastião had contact in Luanda[24].

The farm Tentativa, where Cabral worked, was one of the most important Portuguese possessions overseas and it was ‘a model’ for colonial exploration, especially concerning the ‘scientific’ form of sugar production, or even extracted palm oil[25]. It was owned by the Companhia de Açúcar de Angola, the second largest sugarcane producer in the then colony. During the period in which Cabral was working for this company (1956 to 1957), only at the farm Tentativa about 23,589 tons of sugar were extracted, 308 tons of coconut, and 820 tons of palm oil (dendê oil), thus earning a profit of 1 million dollars[26].

When returning from the farm, in the afternoon, Cabral stopped in Cacuaco to meet with local fishermen and political activists. Sebastião emphasizes that the conversations revolved around the local population’s life, as well as the schooling (and politicization) actions taken along with young people and, finally, the fishermen’s cooperative, founded with the aid of Antônio Jacinto and Mario Antônio. When associating Cabral with his political activity in Cacuaco, Sebastião somehow sought a historical validation and also a significant and key character of anticolonial struggle.

After coming back to Luanda, in the Ingombotas market, Sebastião met him again in Kinaxixe, one of the most famous musseques in the capital[27]. In Kinaxixe, they met young people such as those mentioned above Noé Saúde and Deolinda Rodrigues, besides Deolinda Bebiana.

Meetings we attended and whose keynote was organization for the struggle that was the only way to bring the foreign domination and exploitation in the country to an end. Aimed at the establishment of nuclei of young people decided in the neighborhoods with specific missions, such as clandestine destruction of the economic structures of white men and the youth’s attachment to education, since only those graduated could discuss in equal terms, in the political field, with white men. (SEBASTIÃO, 1993, p. 75)

Within this space, the intentions of the Partido da Luta Unida dos Africanos de Angola (PLUAA) were also announced, the first group in which Sebastião participated and where Cabral was also, somehow, according to Sebastião, associate, since he was one of its founders, in 1956.

In an interview to Oleg Ignatiev (1984), Gabriel Leitão, also an Angolan political activist, said that Cabral played a major role in the PLUAA, selecting among the young candidates to be sent illegally to Algeria, where they would be trained as fighters in future armed units of the MPLA[28]. In turn, Tomas Medeiros, in a testimony to Wilmer Pinto (2014), said that Cabral was one of those responsible for producing anticolonial texts and pamphlets that were disseminated among the musseques. He also participated directly along with Mário de Andrade (former partner of Sebastião in Cacuaco), Agostinho Neto, among others, in the preparation of the Manifesto that later would give rise to the MPLA[29].

According to Dalila Mateus and Álvaro Mateus (2011), this organization was born as a front that brought together people from various political and ideological tendencies and groups, such as the PLUAA, a group that Sebastião helped to found. In this way, he was incorporated into the MPLA, but he did not participate in the founding Board of Directors, rather acting in the rear than in the front line, as evidenced by the event that led to his arrest in 1960[30].

Arrest

In 1960, Adriano Sebastião was arrested along with 38 other Angolans, accused, among other things, of having received in his house in Uíge, where he were transferred to that year, still as a member of the public works sector, a mission of the then incipient MPLA which would go to the then Congo Léopoldville (nowadays Democratic Republic of the Congo) to celebrate its independence.

According to him, at that year (1960) the MPLA was created and this first mission sent to the neighboring country consisted of Bernardo d’Eça de Queirós, Joaquim Bernardo Horácio, Manuel Augusto da Silva Coelho, Domingos Damião Neto, Rodolfo da Ressureição Bernardo, Bernardo Adão, and Alberto Fonseca da Conceição[31]. To move across Angola they disguised as a musical group:

[...] when the Cinco de Junho and only it emerged, a delegation with guitars, mandolins, and the whole bunch of musical instruments with which they played instead of thinking they were clandestine and that they had to leave the borders of Angola as fast as possible, because the Pide, through its buffoons, could know about this trip and do everything to prevent it from happening. The night the delegation arrived we almost did not sleep. Hermengada, my wife, had no hands to measure, as people say, by sewing the papers (documents) they carried, in the linings to prevent it from happening. (SEBASTIÃO, 1993, p. 83)

Three days later, on June 8, the International and State Defense Police (PIDE) held a series of arrests throughout Angola, including the seven individuals who had been in Sebastião’s house a few days before. Sebastião was arrested on June 15 by the police chief of Uíge. These political prisoners in 1960 became known as ‘group of 36,’ despite consisting of 38 people[32]. They went on to serve their sentence in the Bié prison colony and the Missombo prison (Kuando-Kubango).

The group consisted mostly of High School students from the Colégio das Beiras and the Escola Industrial de Luanda, which from the years 1956 to 57 built some form of resistance to Portuguese colonialism through the creation of the movement called Pró-Independência Nacional de Angola, the development of campaigns for literacy, education, and mobilization, thus using the few political texts available to challenge the Portuguese regime[33].

At an event held in February 2006 in Luanda, Adriano Sebastião said that this group would have kept the work initiated by the members of the so-called ‘Processo dos 50,’ developing a ‘hard work’ so that the international community became aware of what was happening in Angola[34].

Coming back to 1960, when Sebastião was arrested, he was asked about the reasons why he got involved with these people, and he answered: “– The Angolan people want the independence of Angola” (SEBASTIÃO, 1993, p. 85).

Final Remarks

Adriano Sebastião died in the year 2010 in Luanda, at the age of 87 years. He was remembered as a ‘man from the MPLA’ and a ‘nationalist,’ as well as due to the fact that in the last years of his life he almost did not criticize the ‘abuse’ of the current president Eduardo dos Santos, who took office more than thirty years ago[35]. Despite these considerations, Sebastião was a man from his age, his memoirs although linked to an ‘official history’ to be told by the MPLA, may also be seen as a collective memory shared by many Angolans who lived in the first half of the 20th century.

His history is important to realize how the oppression of colonialism reached the daily dimension of the Angolans, above all when he reported the persecutions underwent and compulsory work still during his childhood. Access to school education made him a public official and, in this way, we notice in his life story the importance of the native middle layer of the Angolan society in the process of resistance to Portuguese colonialism.

Such resistances should be seen as a multiple and plural procedure that incorporated everything from direct confrontation (organization of trade unions, political movements, etc.) to rather veiled forms of subverting the established colonial order (such as making holes in the fishing nets of Portuguese middlemen, dressing up as musicians to cross the country, etc.), using both local associations (mainly Protestant religious networks, but also Catholic ones) and the broader and supranational networks (e.g. making contact with Amílcar Cabral and the insurgents of the former Congo Léopoldville).

Lastly, it is worth pointing out that Dos campos de algodão aos dias de hoje was also a discourse for Sebastião’s daughters, so that they could recognize their genealogy, the stories and difficulties that their father experienced during his life. In the words of Sebastião himself, “in what I name as dedication, I said that these memoirs were essentially for my daughters so that they could know a little and only a little of the troubled life of their father” (SEBASTIÃO, 1993, p. 137).

References

BITTENCOURT, Marcelo. A criação do MPLA. Estudos Afro-Asiáticos, Rio de Janeiro, v. 32, n.32, p. 185-208, 1997.

BOAVIDA, Américo. Angola: cinco séculos de exploração portuguesa. Civilização Brasileira. 1967.

CASSAMA, Daniel Júlio Lopes Soares. Amílcar Cabral e a independência da Guiné-Bissau e Cabo Verde. 2014. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciências Sociais) - . UNESP, Faculdade de Ciências e Letras., Araraquara, 2014.

CASTELO, Claudia. Novos Brasis" em África: desenvolvimento e colonialismo português tardio. Varia história., v.30, n.53,p. 507-532, 2014

CASTELO, Claudia. Passagens para África: o povoamento de Angola e Moçambique com Naturais da Metrópole. Porto: Edições Afrontamento, 2007.

CASTRO, Isabel Henriques. Território e identidade: O desmantelamento da terra africana e a construção da Angola colonial (c. 1872 – c. 1926). Lisboa, 2003. Sumário pormenorizado da lição de síntese apresentada a provas para obtenção do título de Professor Agregado do 4º Grupo (História) da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa.

CRUZ, Elizabeth Ceita Vera. O Estatuto do indigenato e a legalização da discriminação na colonização portuguesa: o caso de Angola. Lisboa: Novo Imbondeiro. 2005.

FENTRESS, James; WICKHAM, Chris. Memória social. Lisboa: Portugal: Teorema. 1994.

FRANCO, Paulo Fernando Campbell. Amilcar Cabral: a palavra falada e a palavra vivida. 2009. Dissertação (Mestrado em História Social) - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2009

HALBWACHS, Maurice. A memória coletiva. São Paulo: Centauro, 2004.

HAMPATÉ BÂ, A. A tradição viva. In: KI-ZERBO (Coord.). História geral da África I:Metodologia e pré-história da África. São Paulo: Ática; Paris: UNESCO, 2012, p.181-218.

LE GOFF, Jacques. Memória. In: LE GOFF, Jacques. História e memória. 5. ed. Campinas: Editora da UNICAMP, 2003.

MATEUS, Dalila Cabrita e MATEUS, Álvaro. Angola 61 – Guerra Colonial e consequências. Alfragide: Texto Editores, 2011.

MEDINA, Maria do Carmo. Angola: processos políticos da luta pela independência. ed. Coimbra: Almedina, 2005.

MENDES, Afonso. A Huíla e Moçâmedes: considerações sobre o trabalho indígena. Lisboa : Junta de Investigações do Ultramar, 1958.

MENEZES, Solival. Mamma Angola: sociedade e economia de um país nascente. Prefácio de Paul Singer. São Paulo: Edusp; FAPESP, 2000, p. 139.

NASCIMENTO, Washington Santos. Minha mãe me entregou nas mãos do professor para fazer de mim o que quisesse e pudesse?: memórias da educação escolar em Angola. Revista HISTEDBR On-line, v. 55, p. 231-249, 2014.

NASCIMENTO, Washington Santos. Gentes do Mato: os “novos assimilados” em Luanda. 2013. Tese (Doutorado em História Social) - Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Filosofia Letras e Ciências Humanas, São Paulo, 2013

OLEG, Ignatiev. Amílcar Cabral. Moscovo: Edições Progresso.1984.

OLIVEIRA, Mario Antonio Fernandes. Reler África. Instituto de Antropologia. Universidade de Coimbra, 1990

PAREDES, Margarida Paredes. Deolinda Rodrigues, da Família Metodista à Família MPLA, o Papel da Cultura na Política. Cadernos de Estudos Africanos [Online], n.20, 2010, Disponível em: Consultado o 11 Junho 2016

PINTO, Wilmer Delgado Pinto. Caraterização do comando e liderança de Amílcar Cabral. Relatório científico final do trabalho de investigação aplicada. Lisboa: Academia Militar, 2014.

RICOEUR, Paul. A memória, a história, o esquecimento. Campinas/SP: Editora da Unicamp, 2007.

RODRIGUES, Alberto Leite. A indústria química nas colónias: elementos colhidos no cruzeiro de férias (1935). Revista de Chimica Pura Apllicada, Ano 11, n.II, p.67-77, 1936. Disponível em: http://www.spq.pt/magazines/RCPA/487/article/10001262/pdf. Acesso em 10 de Junho de 2016.

SANTOS, Daniel dos. Sociedade política e formação social angolana (1975-1985) Estudos Afro-Asiáticos. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Universidade Cândido Mendes, nº 32, Dez. 1997.

SANTOS, Maria Emilia Madeira dos. Nos caminhos de África: serventia e posse. ICT- Lisboa: Século XIX, 1998.

SEBASTIÃO, Adriano. Mérito do processo 50 foi a consciencialização do povo angolano. Agência Angola Press. Disponível em . Acesso em 02 de Fevereiro de 2016.

SEBASTIÃO, Adriano. Dos campos de algodão aos dias de hoje. Edição do Autor, 1993

SILVA, Elisete Marques. Impactos da ocupação colonial nas sociedades rurais do Sul de Angola, Lisboa: Centro de Estudos Africanos/ISCTE-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, 2003.

Mestre” Tamoda & Kahitu

Notes